The early settlement of South America may have unfolded under harsher climatic conditions than previously believed, according to a recent study published in Nature Communications. This comprehensive examination of the region's archaeological data reveals that the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR) and Younger Dryas (YD) climatic phases did not serve as barriers to human migration but were instead periods of significant cultural development and adaptation.

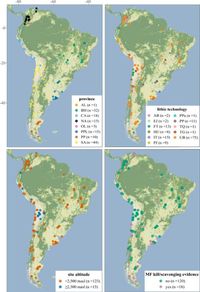

The research, which compiled data from approximately 150 archaeological sites and about 1,700 radiocarbon dates, employed Bayesian chronological modelling to construct a cultural timeline. Findings indicate that human activity likely began in areas most affected by the ACR, particularly in the southernmost and high-altitude regions of South America, defying earlier assumptions that colder climates inhibited settlement.

These climatic phases, dated around 14,700 to 13,000 years ago for the ACR and beginning around 12,900 years ago for the YD, highlight a critical period for human expansion. The authors of the study noted that while much of the Northern Hemisphere experienced significant warming during the Bølling-Allerød, the Southern Hemisphere faced cooling due to the ACR, which theoretically might have retarded human migration. However, the data suggests otherwise.

Key technological advancements, such as bifacial point technology, appear to have occurred before and during the ACR, with evidence indicating that the killing and scavenging of megafauna by humans likely began well before these climatic shifts, around 18,660 to 16,695 years ago. Moreover, the study posits that cultural adaptation over generations allowed human populations to withstand and even thrive despite challenging conditions.

Additionally, results revealed a west-to-east pattern of settlement within the southern Andes, which emerged as an important dispersal route. More widespread human occupation appears to have occurred during or after the YD when climatic conditions began to stabilize, suggesting that a significant lag existed in human adaptation to warming climates compared to their Northern Hemisphere counterparts.

The role of human activity in relation to megafaunal extinctions remains ambiguous. The archaeological dataset did not provide clear evidence linking human activity directly to these extinctions, suggesting that previous models attributing these losses solely to human hunting or climate change may require revision. This fresh perspective opens up further research questions regarding the interplay between early human societies and the megafauna that cohabited the region.

Despite the groundbreaking insights offered by this research, it also highlights the considerable underrepresentation of certain geographical areas in archaeological records, particularly the Guiana Highlands and parts of the Amazon. The authors called for expanded research efforts in these regions, driven by ethical considerations and collaboration with indigenous communities. They emphasized the necessity for comprehensive data reporting to enhance the reliability of cultural timelines and address existing gaps.

In sum, this study enriches our understanding of how early humans navigated the complexities of a changing climate. As Becerra-Valdivia et al. concluded, rather than acting as barriers, the climatic challenges faced during the late Pleistocene may have played a crucial role in shaping human cultures and capabilities, allowing them to adapt, survive, and eventually flourish in various environments across South America.