For the first time in Asian history, a former head of state stands before the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, charged with crimes against humanity. Rodrigo Duterte, the ex-president of the Philippines, faces allegations of orchestrating a brutal campaign that left thousands dead in the name of a war on drugs—a campaign that has drawn fierce debate, deep sorrow, and a desperate search for accountability.

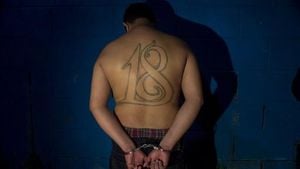

On March 11, 2025, the ICC issued a warrant for Duterte’s arrest, charging him with three counts of murder as crimes against humanity. He was taken into custody shortly thereafter, making headlines across the globe. ICC prosecutor Mame Mandiaye Niang described Duterte as an “indirect co-perpetrator,” asserting that he shared a common plan with others—including police officers—to “neutralize” alleged criminals through violent means, including murder. The charges span both his time as mayor of Davao City and his presidential years, painting a damning picture of systematic violence.

The first charge against Duterte concerns the killings of 19 people in Davao City between 2013 and 2016, when he served as mayor. The second charge relates to the murder of 14 so-called "high-value targets" across the Philippines during his presidency from 2016 to 2022. The third charge addresses the murder and attempted murder of 45 people in village clearance operations, according to the BBC. Prosecutors allege that Duterte and his associates shared a clear agreement to use violent crimes—including extrajudicial killings—to eliminate suspected criminals.

Duterte, now in custody since March 2025, insists he cracked down on drug dealers to rid the country of street crime. He continues to deny wrongdoing, stating the campaign was lawful and that suspects were killed only because they resisted arrest. His lawyer has argued that Duterte’s poor health should preclude him from standing trial, but so far, those pleas have not halted the proceedings.

What makes this case even more extraordinary is the data and testimony supporting the charges. Former Philippine National Police (PNP) chief Gen. Nicolas Torre III has publicly backed the ICC’s case, citing a dramatic spike in killings immediately after Duterte assumed the presidency. Torre, who was then chief of the Regional Operations Division of Police Regional Office 3, described how “it was easy” for him to implement the ICC’s arrest warrant against Duterte. In a Facebook post, he wrote, “While I agree that more suspects were arrested after Duterte took office, what alarmed me was the sudden increase in suspects killed during buy-bust operations, allegedly for fighting back.”

Official statistics bear out his concerns. From January to March 2016, before Duterte took office, police arrested 1,202 suspects with no reported deaths. Between April and June, 10 suspects were killed and 1,074 arrested. But after Duterte’s inauguration on June 30, 2016, the numbers skyrocketed. In July alone, 120 suspects were killed and 1,121 arrested—nearly 10 percent of those apprehended. For the entire third quarter of 2016, 271 suspects were killed out of 3,368 arrested, or about one in every 13. “For me, Duterte’s ‘kill, kill, kill’ policy is clearly reflected in these numbers,” Torre said. “He must answer to the families of Filipinos now seeking justice before the ICC.”

According to #RealNumbersPH, an official government data initiative, authorities conducted 239,218 anti-illegal drug operations, arrested 345,216 people, and reported 6,252 deaths during these operations from July 1, 2016, to May 31, 2022. However, advocacy groups claim the real death toll could exceed 30,000 when vigilante-style killings outside official police operations are included. The Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency’s 2016 report further revealed that of the 34,077 anti-drug operations that year, 21,655 were buy-bust operations and 305 were large-scale raids targeting major drug lords and laboratories.

The human cost behind these numbers is staggering. Maria (a pseudonym), whose husband was killed in 2017 at a crowded terminal in Caloocan City, shared her story with Amnesty International. Her husband, a jeepney driver, was gunned down by two men on motorcycles—a tactic known locally as “riding in tandem.” Witnesses were too afraid to testify, and Maria was forced to focus on survival rather than seeking justice. “No one wanted to sympathize with the family of a tokhang victim,” she recalled, referencing the notorious police operation “Oplan Tokhang.”

Maria’s children were bullied at school, labeled as the offspring of a drug addict. “It felt so heavy when they would come to me crying and saying, ‘Mama, other kids told me that Papa was killed because he was a drug addict. Is that true?’ How could I answer that?” she said. Determined to clear her husband’s name and to fight back against the stigma, Maria became a community organizer with Rise Up for Life and for Rights, a group supporting families of victims. “I have no reason to stay silent. I have no reason to stop,” she said, her resolve clear even as she admitted to moments of exhaustion and self-doubt.

When news broke of Duterte’s arrest, Maria described a surge of hope. “I was screaming in the kitchen, ‘Yes, yes, yes!’” she recalled. For her and many others, the arrest felt like a victory—a validation of years of protest and advocacy. “This is because of us, because of me,” she told her friends, acknowledging the collective struggle of families who dared to speak out despite fear and hardship.

Yet, Maria and other victims’ families remain wary. “We are not just numbers; we are real people, real families. We are not just past victims; we continue to be victimized by a lack of truth, justice and accountability,” she said. She called for protection from reprisals and for policies that protect, rather than target, citizens. “We want protection for ourselves and for our families from any reprisal for speaking up. I hope the ICC sides with the truth. Even as we are unable to obtain justice here in our own country, we are grateful for anyone who can give us some hope.”

Despite mounting pressure from rights groups and victims’ families, the Philippine government has not formally cooperated with the ICC investigation. The court’s authority to arrest suspects is limited without the cooperation of national governments—a frequent stumbling block in international justice. Still, Duterte’s unprecedented indictment and arrest have sent shockwaves through the region, signaling a new era for accountability in Asia.

As the world watches the proceedings in The Hague, the families of the slain, advocates, and critics alike wonder: will this case finally bring justice for the thousands who lost their lives in the Philippines’ war on drugs? For now, the story continues—one of pain, hope, and an unwavering demand for truth.