In a year marked by mounting economic anxiety and fierce debate over generational equity, two stories—one global, one local—are converging to spotlight the struggles of young adults trying to find their footing. On one hand, leading economists are warning that entrenched policy decisions in the UK and France have deepened intergenerational divides, while on the other, New Hampshire’s housing crisis is providing a stark example of how these tensions play out in everyday life.

Albert Edwards, the outspoken global strategist at Société Générale, has never shied away from controversy. On September 15, 2025, he took to LinkedIn to sound the alarm about what he sees as a looming fiscal disaster, fueled by what he calls "Boomer-driven spending habits" in the UK and France. Citing "shocking charts" from Financial Times data journalist John Burn-Murdoch, Edwards argued that government spending on citizens over 65 has reached unsustainable levels. "Inter-generational tension is not just because boomers have got rich from QE driving asset prices higher, especially housing," Edwards wrote, referencing the U.S. Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing policies after the 2008 and 2020 financial crises. He contends these policies have inflated asset prices, disproportionately benefitting older, wealthier populations.

According to Edwards, the data shows that policy choices are "robbing the young to soothe the old." He didn’t mince words: "In the UK and especially France, pensioners have broken the public finances in two of the countries who can least afford it. Bonkers!" For Edwards, the solution is drastic: "We ‘need’ a fiscal crisis for politicians to be able to act." He believes only a true crisis will force leaders to confront what he sees as decades of mismanagement and political submission to Baby Boomer interests.

Edwards’ warnings are not new. The Financial Times’ Alphaville section describes him as a "provocative and voluble strategist," best known for his "ice age" theory, which predicts that Japan-style economic stagnation will eventually hit the West. He has long been a "permabear" on stocks, and in 2024 he reminded Alphaville that he first saw the warning signs back in 1996. "What was playing out in Japan would also play out in the west, with a lag … basically like the secular stagnation thesis," he said. This idea, revived by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers in 2013, posits that slower population growth and less technological progress will hold back wage increases and economic expansion—an idea first floated by economist Alvin Hansen in the 1930s.

Yet the world of 2025 looks very different from the stagnant, zero-interest-rate environment of the 2010s. Inflation has been running hot, and nearly full employment has characterized the U.S. economy since the pandemic recovery. Still, young workers globally are facing a rising sense of "despair," according to economists David Blanchflower and Alex Bryson, who told Fortune that the classic midlife crisis is being replaced by a new, earlier malaise. Their research suggests that it’s not falling wages or unemployment driving this trend; in fact, the ratio of youth wages to older workers has improved, and real wages are up. Instead, it’s the skyrocketing costs of housing, healthcare, and student debt that are pushing young adults to the brink. Blanchflower said, "this job sucks," summarizing the sentiment of many young workers. He also noted a "worsening of reported mental health since the mid-2010s."

These intergenerational tensions are not just a Western phenomenon. In Asia, they have reached a boiling point. The Financial Times reports that a "Gen Z" protest in Nepal, sparked by bans on social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, escalated to the point where Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli resigned. The paper describes a "growing regional trend" where older leaders are clashing with "disenfranchised, ambitious and often unemployed young people who are fed up with politics as usual and a lack of opportunities." Nepal’s median age is just 25, and similar youth-led uprisings have erupted in Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Bangladesh in recent years.

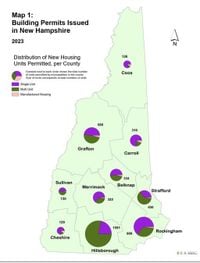

Back in the U.S., the housing crisis in New Hampshire offers a ground-level view of these global tensions. As of September 14, 2025, the state faces a severe shortage, needing to build 90,000 new units over the next two decades to meet demand, according to a recent analysis by the New Hampshire Department of Business and Economic Affairs (NH BEA). The department, working with ESI-Econsult Solutions Inc., developed a fiscal housing calculator to assess the impact of housing development on taxpayers through 2040. "This is the only resource that looks at the fiscal impact of various kinds of housing on municipal budgets," said Lorna Colquhoun, communications deputy director at NH BEA.

The 2023 New Hampshire Statewide Housing Needs Assessment Report paints a bleak picture: the rental vacancy rate is almost 5 percent, the owner vacancy rate is just under 2 percent, and the state needs 60,000 new units by 2030 just to keep up. In Manchester, the largest city, the population of 115,420 needs 8,738 additional housing units by 2040—on top of the current 49,550. Nashua, with a median income of $92,460 and 91,130 residents, faces a shortfall of 6,272 units.

For young residents, the situation is dire. "I moved to New Hampshire from the Midwest thinking that it would be cheaper, given how rural New Hampshire is," said Christopher Knapp, a 29-year-old Manchester resident. Instead, he found rents rising rapidly and a housing market that’s anything but affordable. Manchester alone accounted for about 20 percent of statewide evictions in 2023, and there are no laws restricting rent increases—even mid-lease. "I hear from neighbors who’ve lived in New Hampshire long enough, and they tell me that rent for the same two-bed I live in was almost $1,000 cheaper a few years ago. How are people my age supposed to save up to buy a house?" Knapp asked.

Others, like Ashlee, another 29-year-old in Manchester, echo the frustration. "Trying to find a place has been a real pain," she said, describing her struggle to move out of a nearly $3,000, three-bedroom unit shared with roommates. Many of the so-called three-bedroom apartments are actually two bedrooms and a spare room, she noted. "Most of these apartments are too expensive and don’t include any utilities."

Local zoning laws are making things worse. Last year, Republicans in the state legislature blocked a bill to expand accessory dwelling units, arguing it would lower property values. But new bipartisan efforts in 2025 aim to loosen restrictions, expand ADUs, prevent towns from imposing minimum lot sizes, and allow residential development in commercial zones. "I believe the state has begun to take some steps to reform housing availability," said Thomas Fougere, an engineer in his 20s. "But a big part of the issue is local municipalities. Strict zoning ordinances prevent building in towns adjacent to large populated areas."

Albert Edwards, for his part, sees a broader crisis looming if these issues aren’t addressed. In April 2023, he warned of "Greedflation"—the phenomenon of companies raising prices excessively and threatening the fabric of capitalism itself. "The end of Greedflation must surely come," he wrote, warning that policymakers could no longer ignore the problem. He even floated the controversial idea of price controls, despite having "weakening confidence" in how capitalism was working.

Whether the answer lies in fiscal crises, legislative reforms, or a fundamental rethinking of capitalism, one thing is clear: the economic struggles of young people are no longer just a personal problem. They are a political and social flashpoint, demanding urgent attention from leaders at every level.