When most people hear the word "mummy," their minds dart straight to Egypt — pharaohs, pyramids, and linen-wrapped rulers entombed with golden treasures. But a groundbreaking new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on September 15, 2025, is rewriting the story of mummification. Researchers have unearthed what they believe are the world’s oldest known mummies in southeastern Asia, dating back up to an astonishing 12,000 years. That’s nearly twice as old as the famous Egyptian mummies, and it even predates the previously oldest known mummies from the Chinchorro culture in South America by several millennia.

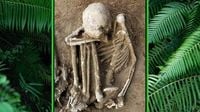

The discovery is the result of years of detective work by an international team led by the Australian National University. The group examined 54 sets of human remains from archaeological sites spread across southern China, Vietnam, and, to a lesser extent, the Philippines, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. These remains were found buried in tightly crouched or squatting positions, often with telltale signs of burning or cuts. According to NBC News, the bones came from pre-Neolithic burials dated between 14,000 and 4,000 years ago, with the largest number of samples hailing from Vietnam and China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

What set these remains apart was the evidence of deliberate preservation. Using advanced, nondestructive techniques such as X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy, the scientists found that the skeletons’ discoloration wasn’t the result of cremation or direct burning. Instead, the bones had been exposed to a low-oxygen, smoky environment — the result of a smoke-drying process carried out over fire. “These patterns represent a coherent and intentional framework for treating the dead,” the researchers wrote in their study, as reported by Mental Floss. The process, they concluded, was a purposeful act of mummification performed by ancient hunter-gatherer communities.

Why go to such lengths to preserve the dead? The answer, it seems, lies deep in the human desire to maintain a connection with loved ones. As study author Hirofumi Matsumura of Sapporo Medical University told Agence France-Presse, the practice “allowed people to sustain physical and spiritual connections with their ancestors, bridging time and memory.” Hsiao-chun Hung, the study’s lead author and a senior research fellow at the Australian National University, echoed this sentiment, explaining to Live Science that “the practice prolonged the visible presence of the deceased, allowing ancestors to remain among the living in a tangible way, a poignant reflection of enduring human love, memory and devotion.”

This ancient tradition wasn’t just about holding on to memories. The researchers believe the smoke-drying ritual carried spiritual, religious, or cultural meanings that went far beyond simply slowing decay. In some communities, it was believed that the spirit could roam freely during the day and return to the body at night, offering a powerful way for the living to interact with the dead. “I believe this reflects something deeply human — the timeless wish that our loved ones might never leave us, but remain by our side forever,” Hung told Agence France-Presse.

Interestingly, the Southeast Asian mummies bear a striking resemblance to those found in Australia and Papua New Guinea. In both regions, bodies were often prepared in crouching positions and preserved using smoke. Some Indigenous communities in Australia and Papua New Guinea continue to practice smoke-drying and mummification even today, a tradition that persisted in Papua New Guinea as late as the 1950s, according to Mental Floss. In fact, the research team visited Indonesia’s Papua province in 2019 to observe the Dani people as they mummified bodies by binding them tightly and smoking them until they turned black — a custom that may be a direct continuation of ancient practices.

Could this suggest a shared cultural tradition stretching back tens of thousands of years? The researchers think it’s possible. As they note in the study, the similarities among smoked mummies from southern China, New Guinea, and Australia might signal “a shared cultural tradition, one that could potentially go back as far as the early expansion of Homo sapiens from Africa through tropical latitudes of southern Asia,” a migration that began more than 60,000 years ago. Of course, as the team acknowledges, these parallels might also be coincidental — after all, fire is a universal tool, and many cultures have used it in funerary rites for reasons both practical and symbolic.

The graves examined in the study contained only bones, with no preserved skin or hair. While smoke-drying would have kept soft tissues intact for decades or even centuries, these bodies — unlike their Egyptian counterparts — were not sealed in containers, so their preservation was ultimately temporary. Some of the bones showed signs of being heated to more than 900 degrees Fahrenheit, suggesting that, in some cases, burning may have gone beyond mere smoking. Michael Green, an archaeologist interviewed by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, cautioned that “multiple cultures treated corpses with fire, without smoking or preserving them,” and that not every instance of heated bones points to mummification.

Before this study, the title of “oldest known mummies” belonged to the Chinchorro people of modern-day Peru and Chile, who began mummifying their dead around 7,000 years ago. The Chinchorro used a very different approach, removing organs and stuffing corpses with natural fibers before drying them in the desert. In contrast, the Egyptians began their iconic embalming rituals around 2600 BCE, continuing for centuries. As Professor Salima Ikram, an expert in Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, pointed out to NBC News, “The term has been taken on by other groups to identify other preserved bodies. So it’s got a much more general understanding now.” She added, “What is nice is that the idea behind it is similar, because they wanted to preserve the body.”

The findings have not gone unchallenged. Some experts, like Rita Peyroteo Stjerna of Uppsala University, who was not involved in the research, cautioned that the dating methods could have been more robust and that it’s not yet clear if all the mummies were consistently smoke-dried across the various locations. Nevertheless, she told Agence France-Presse that the discoveries offer “an important contribution to the study of prehistoric funerary practices.”

So, what does all this mean for our understanding of ancient civilizations? For one, it shatters the notion that mummification was the exclusive domain of the Egyptians or South Americans. Instead, it reveals a rich and ancient tradition in Asia — one that may have been practiced by hunter-gatherer societies for thousands of years, linking the living and the dead across continents and millennia. As Hung put it, “The fact that smoke-dried mummification spread across such a vast area and endured for more than 12,000 years among Indigenous groups is remarkable.”

In the end, these ancient mummies remind us that the urge to remember, honor, and keep our loved ones close — even after death — is as old as humanity itself, transcending borders, cultures, and time.