Peru, a country crisscrossed by mountain ranges and nestled along the volatile Pacific coastline, has once again felt the tremors that define its geological reality. Over the course of October 8th and 9th, 2025, three moderate earthquakes shook different regions of the nation, serving as a reminder of the ever-present risks posed by seismic activity. According to official reports from the Geophysical Institute of Peru (IGP) and the National Seismological Center, these recent events—though not disastrous—underscore the importance of preparedness, vigilance, and public education in a country perched atop the infamous Pacific Ring of Fire.

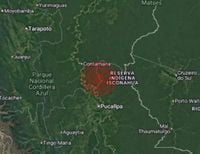

The most significant of these recent earthquakes struck at 8:42 a.m. local time on October 9, 2025. The IGP registered a magnitude of 4.5 on the Richter scale, pinpointing the epicenter 64 kilometers southeast of Contamana, straddling the border between the Ucayali and Loreto regions. The quake originated at a depth of 162 kilometers, a factor that helped to dampen its impact at the surface. Residents in Contamana reported feeling a light to moderate shaking—classified as intensity II-III—yet, crucially, there were no reports of injuries or material damage. As the IGP noted, the substantial depth of the earthquake played a decisive role in mitigating its effects.

Just hours earlier, at 5:05 a.m., another tremor was recorded 21 kilometers northwest of Zorritos in the Contralmirante Villar province of Tumbes. This earthquake, measuring 3.7 in magnitude and reaching a depth of 22 kilometers, was also felt with an intensity of II-III. Again, no casualties or damage were reported, but the event was enough to rattle nerves and reinforce the necessity of readiness in these coastal communities.

The seismic sequence began the previous evening, October 8, at 8:43 p.m., with a magnitude 4.1 earthquake occurring 74 kilometers west of Pastaza in the Loreto region. With its epicenter buried 114 kilometers beneath the surface, this quake, too, spared the region from harm, causing neither injuries nor destruction. All three quakes were swiftly detected and reported by the National Seismological Center and the IGP, whose monitoring networks span the breadth of the country.

Why are these tremors so common in Peru? The answer lies deep beneath the surface. Peru sits atop a collision zone between the Nazca and South American tectonic plates—a geological frontline where the relentless push and grind of the earth’s crust generates frequent seismic activity. As Hernando Tavera, president of the IGP, explained to RPP Noticias, "All seismic activity in Peru is produced by the collision or convergence of the Nazca Plate with the South American Plate. This process is practically a scenario of frontal collision between two plates." This tectonic ballet is part of the broader Pacific Ring of Fire, a horseshoe-shaped zone stretching for 40,000 kilometers and responsible for more than 80% of the world’s earthquakes and a large share of its volcanic eruptions.

Over the years, Peru has experienced the full spectrum of seismic events—from minor tremors that barely rattle windows to catastrophic earthquakes that leave deep scars. The largest earthquake recorded by instruments in Peru occurred on October 3, 1974, when a magnitude 8.0 quake struck Lima and much of the southern coast. That disaster lasted around 90 seconds and resulted in 252 deaths and over 3,600 injuries, a stark reminder of the stakes involved.

Despite the country’s seismic pedigree, it’s worth noting that not all tremors are created equal. As Tavera clarified, the terms "earthquake," "tremor," and "seismic event" are often used interchangeably, but in Peru, "we use the word 'terremoto' when the movement causes human losses and material damage, such as the collapse of houses. We call it 'temblor' when it simply shakes the ground and nothing happens." The technical term, he emphasized, is "sismo." Furthermore, he debunked a common myth, stating, "It is not true that several small earthquakes can release enough energy to prevent a larger one." Instead, the accumulation and sudden release of seismic energy remain unpredictable, reinforcing the need for continuous preparedness.

Preparation is a theme echoed by every authority and news outlet covering these recent quakes. The IGP and the National Institute of Civil Defense (Indeci) stress the importance of building a culture of prevention. This means more than just knowing the emergency numbers—though those are vital: 105 for general emergencies, 116 for firefighters, 110 for highway police, 115 for civil defense, 113 for health information, and 106 for ambulance services. It means regular participation in evacuation drills, securing heavy furniture, keeping exits clear, and—crucially—never using elevators during or immediately after a quake. As El Comercio explained, elevators can detach from their structures and fall, posing a grave risk if used during seismic events.

One of the most practical steps families can take is preparing an emergency kit, or "mochila de emergencia." This kit should include water, non-perishable food, a flashlight, a battery-powered radio, a first aid kit, and a blanket, tailored to the specific needs of each household. The IGP recommends having a kit for every two people, as well as a reserve box with supplies to last several days. These should be stored in accessible, safe locations, and adapted for children, the elderly, pregnant women, or those with chronic illnesses or disabilities.

Technology also plays a role in modern preparedness. Google’s early earthquake alert system, for example, can be activated on mobile devices by navigating to the "Emergency" settings and enabling "Earthquake Alerts." Such tools, combined with the IGP’s real-time updates on social media, help keep the public informed and ready to act at a moment’s notice.

Education remains a cornerstone of resilience. Schools, workplaces, and homes are encouraged to identify safe zones, participate in drills, and assign roles to each family member as part of a comprehensive emergency plan. After a quake, authorities recommend checking for structural damage, avoiding the use of matches or candles, and following official updates via portable radios. For coastal residents, moving away from the sea until tsunami risks are ruled out is essential, as only the strongest earthquakes (magnitude 7 or above) typically generate dangerous waves.

Ultimately, the recent cluster of earthquakes in Ucayali, Loreto, and Tumbes may not have left visible scars, but they have reinforced a crucial message: seismic events are an inescapable part of life in Peru. The country’s ability to withstand and recover from such shocks depends on the vigilance of its people, the rigor of its institutions, and the strength of its collective memory. Each tremor is a nudge—a reminder to prepare, to educate, and to respect the powerful forces that shape the land beneath our feet.