In a groundbreaking effort to combat the relentless poaching crisis threatening South Africa's rhino population, the University of the Witwatersrand has launched the Rhisotope Project, a novel anti-poaching initiative that involves injecting rhino horns with radioactive isotopes. This pioneering campaign, officially launched on July 31, 2025, aims to make it significantly harder for poachers and traffickers to smuggle rhino horns across international borders by leveraging existing nuclear security infrastructure.

The Rhisotope Project is the culmination of six years of meticulous research and testing, which began with a pilot study involving 20 rhinos at the UNESCO Waterberg Biosphere Reserve. These rhinos were carefully injected with low-dose, non-toxic radioactive isotopes embedded within their horns. Extensive veterinary examinations and blood tests confirmed that the radiation levels used are completely safe for the animals, causing no harm or DNA damage. As Professor James Larkin, Chief Scientific Officer of the Rhisotope Project and director of the Radiation and Health Physics Unit at Wits University, explained, "We have demonstrated, beyond scientific doubt, that the process is completely safe for the animal and effective in making the horn detectable through international customs nuclear security systems." He added reassuringly, "No, it will not harm the animals and, no, they won't glow in the dark."

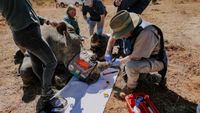

The process itself is surprisingly straightforward. According to Larkin, it involves drilling a small hole into the rhino's horn, inserting the carefully selected radioactive isotope in a couple of spots, sealing the horn, and then reversing the tranquilizer—all completed within minutes. The injected isotopes emit radiation strong enough to trigger alarms on radiation detectors installed worldwide at airports, seaports, and border crossings. These detectors, originally designed to prevent nuclear terrorism, are now being repurposed to identify smuggled rhino horns, even when concealed inside full 40-foot shipping containers. Larkin noted, "Even a single horn with significantly lower levels of radioactivity than what will be used in practice successfully triggered alarms in radiation detectors." To ensure the technology's effectiveness, the team also tested 3D-printed rhino horns with identical keratin properties, simulating various transport scenarios such as carry-on luggage, air cargo shipments, and priority parcel deliveries, all of which successfully triggered detection systems.

South Africa, home to the world's largest rhino population estimated at around 16,000, faces a persistent poaching crisis with roughly 500 rhinos killed annually for their horns. This is part of a broader, devastating decline in rhino numbers worldwide—from an estimated 500,000 at the start of the 20th century to approximately 27,000 today—largely driven by demand in Asian markets. Rhino horns are prized not only for their role in traditional medicine but also as status symbols among wealthy individuals.

Despite a slight dip in poaching numbers in recent years—for instance, in 2024, 420 rhinos were poached in South Africa, marking a 15 percent decrease from the previous year—the threat remains grave. White rhinos are classified as near threatened, while black rhinos are critically endangered, with the latter experiencing a 1 percent population decline due to poaching, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The Rhisotope Project represents a crucial, proactive step in rhino conservation. Unlike reactive measures, this initiative aims to deter poachers by increasing the risk of detection and interception. Jamie Joseph, director of the Saving the Wild charity, praised the project as "innovative and much needed," emphasizing that while it is not the ultimate solution, it can disrupt illegal horn trafficking and provide valuable data to map these illicit networks.

Joel Berger, a wildlife ecologist at Colorado State University who is not directly involved with the project, welcomed the initiative as an exciting use of new technology to protect these iconic species. However, he cautioned that such technological interventions must be paired with stronger law enforcement efforts to dismantle the criminal networks behind rhino horn trafficking. "It's not enough on its own to save the rhinos," Berger said, underscoring the need for comprehensive strategies.

International support for the Rhisotope Project is strong. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which collaborated on the initiative, highlighted its innovative use of nuclear science to address global challenges. IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi stated, "By leveraging existing nuclear security infrastructure, we can help protect one of the world’s most iconic and endangered species." This collaboration between nuclear energy officials, conservationists, and academic researchers exemplifies a multidisciplinary approach to conservation.

Since the official launch, five additional rhinos have been injected, marking the beginning of what the university hopes will be a mass deployment of the technology across South Africa's rhino population. The Rhisotope Project operates as a registered nonprofit and actively encourages private wildlife park owners, national conservation authorities, NGOs, and conservation groups to participate and have their rhinos treated promptly.

Jessica Babich, CEO of the Rhisotope Project, emphasized the broader significance of the effort: "Our goal is to deploy the Rhisotope technology at scale to help protect one of Africa’s most iconic and threatened species. By doing so, we safeguard not just rhinos but a vital part of our natural heritage."

While de-horning rhinos has been another method employed to reduce poaching—studies show it can cut poaching by 78 percent over seven years—it has drawbacks, including altering rhino behavior and social dynamics. The Rhisotope Project offers a less intrusive alternative that maintains the animal's natural state while enhancing the detectability of horns if poached.

As the global community watches closely, the Rhisotope Project stands as a beacon of hope in the fight against wildlife crime, demonstrating how science and innovation can intersect to protect endangered species. Yet, the success of this initiative will depend on widespread adoption, robust enforcement, and continued vigilance against the persistent threat of poaching.