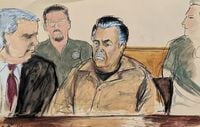

Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, once one of the most elusive and powerful figures in the world of organized crime, has finally faced justice in a New York courtroom. On Monday, August 25, 2025, Zambada, co-founder of the notorious Sinaloa cartel, pleaded guilty to a sweeping set of charges—24 counts in total—including murder, drug trafficking, and racketeering, as reported by Border Report and confirmed in a Department of Justice update published August 29, 2025.

Zambada, now 77, admitted in open court to leading a criminal enterprise that spanned decades and continents. His organization, the Sinaloa cartel, is recognized by U.S. authorities as the largest and most violent drug-trafficking group on the planet, operating on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. The cartel’s reach, according to AFP, extended into the heart of American cities, flooding them with cocaine, fentanyl, and other deadly narcotics. The impact of Zambada’s operations has been devastating, fueling the opioid crisis and leaving a trail of violence in its wake.

As part of his plea agreement, Zambada avoided the death penalty but faces life imprisonment at a sentencing hearing to be determined. More strikingly, he agreed to forfeit $15 billion in ill-gotten gains—a staggering sum that reflects the scale of his criminal empire. The forfeiture isn’t just a number on paper: if Zambada cannot pay the full amount, he has agreed to surrender any property he owns until the debt is settled, according to Border Report.

Zambada’s courtroom confession was as chilling as it was comprehensive. He admitted to starting his criminal career at age 19, planting his first marijuana crop before moving on to far more lucrative—and lethal—endeavors. Over the years, Zambada acknowledged transporting 500 tons of cocaine to the United States, earning hundreds of millions of dollars annually. He also confessed to ordering the assassinations of rivals. In his own words, “many innocent people died as well.”

The breadth of Zambada’s corruption was laid bare. He described bribing countless police officers, military officials, and politicians in Mexico to protect his operations. This claim, though not directly addressed by Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum in her public statements, underscores the deep-seated influence the Sinaloa cartel has wielded over Mexican institutions for decades.

Just months before his arrest, prosecutors revealed, Zambada ordered the murder of his own nephew—an act emblematic of the ruthless discipline he imposed within his organization. His private security force, equipped with military-grade weapons, operated with the efficiency and brutality of a paramilitary unit. The cartel’s corps of “sicarios,” or hitmen, carried out assassinations, kidnappings, and torture on a scale that shocked even seasoned investigators.

Zambada’s downfall began in July 2024, when he was taken into custody after arriving at a Texas airport on a private plane alongside the son of fellow cartel founder Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. The arrest marked the end of a two-decade manhunt by U.S. law enforcement. According to AFP, Zambada’s capture followed a period of violent infighting within the cartel, with factions loyal to him clashing with those aligned with the "Chapitos," Guzmán’s sons. In some instances, the violence reportedly reached grotesque extremes, with victims allegedly "fed dead or alive to tigers," as U.S. prosecutors described.

Despite Zambada’s conviction and the earlier fall of "El Chapo," speculation that the Sinaloa cartel’s days are numbered may be premature. Mexico’s Security Secretary Omar Garcia Harfuch cautioned in a press conference on August 27, 2025, that while some cartel factions have been weakened, "the organization is far from finished." The cartel’s deep roots, vast resources, and adaptability have allowed it to survive the loss of key leaders before.

Meanwhile, the fate of Zambada’s fortune has become a matter of international debate. During her daily news conference on August 27, 2025, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum announced that she would formally request the United States to share any assets recovered from Zambada’s forfeiture with Mexico’s poorest citizens. "If the United States government were to recover resources, then we would be asking for them to be given to Mexico for the poorest people," Sheinbaum said, as reported by AFP. She doubled down on her stance, telling reporters, "If there is a seizure of assets, obviously, we will be asking for damages. It will be spread among the public, the most humble in our country will get it."

Sheinbaum’s call for reparations reflects a broader debate about the cross-border impact of drug trafficking and the responsibility of both nations to address the damage inflicted on their societies. Mexico, she argued, deserves a portion of Zambada’s wealth, given the suffering his cartel has caused among its people. The issue is not merely symbolic: if the U.S. enforces the $15 billion forfeiture, how that money is distributed could have real consequences for communities devastated by cartel violence and addiction.

Yet, as the legal process unfolds, questions remain. Zambada’s admission of widespread bribery raises uncomfortable issues about the depth of cartel influence in Mexico. While President Sheinbaum has focused on the potential for asset recovery to benefit the poor, she has not publicly addressed Zambada’s claims about corrupt officials. The silence has not gone unnoticed by observers, some of whom see it as a sign of the challenges that still lie ahead in rooting out institutional corruption.

For the United States, Zambada’s conviction is a major victory in the ongoing fight against international drug trafficking. The Sinaloa cartel, declared a terrorist group by Washington, remains a primary target for American law enforcement. The extradition of high-profile figures like Zambada and Guzmán is part of a broader strategy to disrupt cartel leadership and dismantle their operations. Still, as history has shown, removing one kingpin rarely spells the end for such vast criminal enterprises.

On the ground in Mexico, the struggle continues. The violent conflicts between rival cartel factions have not abated, and the flow of drugs across the border remains a persistent threat. The Sinaloa cartel’s ability to adapt, fragment, and regroup has kept authorities on both sides of the border on high alert. As new leaders emerge and old alliances shift, the battle against organized crime shows no signs of letting up.

Zambada’s guilty plea and the unprecedented $15 billion forfeiture mark a turning point in the saga of the Sinaloa cartel. Yet, for the families affected by drug violence, for the communities struggling with addiction, and for the governments striving to restore order, the story is far from over. The question now is whether this moment will lead to real change—or simply mark another chapter in a conflict that has already claimed too many lives.