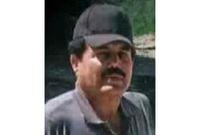

In a historic courtroom moment on August 25, 2025, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, the legendary Mexican drug lord and co-founder of the Sinaloa cartel, pleaded guilty to sweeping federal charges in Brooklyn, New York. The plea marks the dramatic downfall of a kingpin whose criminal career spanned over half a century and whose shadow loomed large over the global narcotics trade.

Zambada, now 77 and reportedly in poor health, admitted to engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise for 35 years, beginning in 1989, and to racketeering conspiracy. According to BBC and ABC News, he acknowledged running the Sinaloa cartel with Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán, overseeing the shipment of at least 1.5 million kilos of cocaine, along with heroin, fentanyl, and other drugs, into the United States since the 1980s.

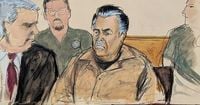

Standing before Judge Brian Cogan, Zambada delivered a statement that was both confessional and remorseful. "I started getting involved with illegal drugs in 1969 when I was 19 years old when I planted marijuana for the first time," he said, reading from a prepared text. "I went on to sell heroin and other drugs, especially cocaine." Through a Spanish-language interpreter, he added, "I recognize the great harm illegal drugs have done to the people in the United States and Mexico. I apologize for all of it, and I take responsibility for my actions." (Associated Press)

His admissions didn’t stop at drug trafficking. Zambada openly conceded to the violence that underpinned his empire. "I directed people under my control to kill others to further the interests of my organization," he admitted, referencing the deadly Mexican drug wars of the 1980s and 1990s. He acknowledged that "many innocent people" lost their lives as a result. According to Mexican media cited by BBC, he further confessed, "the organization that I headed fed corruption in my country by paying police, military commanders and politicians who allowed us to operate freely."

The plea agreement is severe: Zambada must forfeit $15 billion, a staggering sum reflecting the immense profits of his criminal enterprise. Sentencing is set for January 13, 2026, and Judge Cogan indicated a life sentence awaits the former kingpin. U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi, speaking at a press briefing, called the guilty plea a "landmark victory" for the Department of Justice. "El Mayo will spend the rest of his life behind bars. He will die in a U.S. federal prison where he belongs," Bondi declared, as reported by Reuters and ABC News. "His guilty plea brings us one step closer to achieving our goal of elimination of the drug cartels and the transnational criminal organizations throughout this world that are flooding our country with drugs, human traffickers and homicides."

The road to Zambada’s arrest was as dramatic as his criminal career. In July 2024, he was lured onto a plane by Joaquín Guzmán López, one of El Chapo’s sons, under the pretense of inspecting a clandestine airfield in Mexico. Instead, the aircraft landed at a small airstrip near El Paso, Texas, where U.S. law enforcement was waiting. Both men were taken into custody. There are conflicting reports about the circumstances—Zambada’s lawyer claims Guzmán López kidnapped him, while the Guzmán family denies this. Regardless, the arrest marked the end of an era. (Al Jazeera, BBC)

Zambada’s guilty plea follows the conviction and life sentence of his former partner, El Chapo, in 2019. The Sinaloa cartel, once united under their leadership, has since splintered into rival factions—one led by Zambada’s descendants and the other by El Chapo’s sons, known as "Los Chapitos." This split has fueled ongoing violent conflict, particularly in Sinaloa state. Zambada’s defense attorney, Frank Perez, emphasized that the plea agreement contains no cooperation component: "He recognizes that his actions over the course of many years constitute serious violations of the United States drug laws, and he accepts full responsibility for what he did wrong. The agreement that he reached with the U.S. authorities is a matter of public record. It is not a cooperation agreement, and I can state categorically that there is no deal under which he is cooperating with the United States Government or any other government."

Perez also relayed Zambada’s appeal to his home state: "He calls upon the people of Sinaloa to remain calm, to exercise restraint, and to avoid violence. Nothing is gained by bloodshed; it only deepens wounds and prolongs suffering. He urges his community to look instead toward peace and stability for the future of the state."

The case against Zambada was built on indictments in both New York and Texas, with the Texas case transferred to New York ahead of the plea. U.S. prosecutors detailed how the Sinaloa cartel, under Zambada’s command, employed thousands of people across Central and South America, Mexico, and the United States. These operatives ensured a steady flow of drugs across the border, maintained relationships with Colombian producers, and orchestrated logistics by land, sea, and air. The cartel’s operations were protected by a militarized cadre of hitmen, and corruption was rampant—bribes were paid to law enforcement and politicians at every level.

In a broader context, Zambada’s plea comes amid heightened pressure from the U.S. government on Mexico to crack down on powerful drug organizations. As Al Jazeera reported, Mexico recently extradited more than two dozen suspected cartel members to the U.S., following assurances from the Justice Department that the death penalty would not be sought for Zambada or other aging kingpins like Rafael Caro Quintero.

Zambada’s story is one of both criminal ingenuity and ruthless pragmatism. For decades, he managed to evade arrest, often operating in the shadows while other cartel leaders, like El Chapo, became notorious for headline-grabbing escapes. But as age and ill health caught up with him, and as the U.S. government closed in, even El Mayo could not outrun justice forever.

After decades atop one of the most sophisticated and violent criminal networks in the world, Zambada’s courtroom confession marks the end of an era. The legacy of the Sinaloa cartel, however, continues to cast a long shadow over Mexico and the United States, with the struggle for control—and for peace—far from over.