Australia's climate during the terminal Pleistocene, approximately 12,000 years ago, is gaining clarity through the latest findings from high-resolution climate modeling. Research employing the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model has produced unprecedented insights into the climate patterns of Sahul, the landmass that includes Australia, New Guinea, and several islands in the region, at a time when early Aboriginal populations were beginning to establish stable settlements. This period marks a transition from the glacial conditions to a warmer, more habitable climate that eventually led to a vibrant ecosystem.

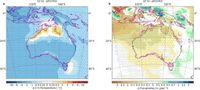

The modeling reveals that while temperatures in the south of Sahul were generally 0.25 to 2°C cooler than pre-industrial levels, certain regions in the central and western equatorial tropics experienced warmer conditions, particularly during the austral spring. This nuanced view of the climate challenges previous assumptions that focused solely on broad trends, allowing a more detailed understanding of the environmental conditions early Australians faced.

Historically, the reconstruction of Australia’s climate has presented inconsistencies, especially regarding the behavior of the monsoon and its implications for local ecosystems. “Existing interpretations of these climates have insufficient spatial or temporal resolution to accurately describe the effects on Aboriginal populations,” the authors noted. This new downscaled modeling effort, which brings the horizontal resolution to an impressive 50 kilometers, enables researchers to quantify climate variability and its impacts effectively.

A significant aspect of the research was the simulation of precipitation patterns, which highlighted that annual rainfall anomalies were heterogeneous across Sahul. The study showed that many areas faced drier conditions compared to pre-industrial times, specifically in the tropical regions. For example, summertime precipitation shifted equatorward, resulting in an average decrease of 1.5 millimeters per day in parts of Sahul's northern regions. The findings thus suggest that the climate could have significantly impacted the migration and settlement patterns of Aboriginal populations as they adapted to changing environmental conditions.

Additionally, the modeling identified how the Australian monsoon, essential for regional rainfall, was active during this timeframe but with a diminished intensity. The area affected by the monsoon reduced dramatically from 2.47 million square kilometers in the pre-industrial period to just 1.06 million square kilometers at 12 ka, indicating how climatic conditions shifted southward, limiting the monsoon's reach. This reduction may have forced early Aboriginal populations to seek more hospitable areas as they navigated the changing landscape.

Further analyses pointed out the role of geographical features in shaping climate responses. The model showed that temperatures were relatively cooler by up to 2°C in the south but displayed variability across different seasons. Notably, temperatures were correlated with insolation anomalies, with peaks notably in spring, attributed to changes in ocean currents and climatic features affecting rainfall distributions.

The researchers argue that the robust simulation results illuminate key differences between historical climate models used in past studies and the detailed picture offered by this high-resolution approach. Earlier studies were hampered by coarse resolutions, which failed to capture critical regional variations—an aspect that the current modeling satisfactorily addressed. This technical advancement emphasizes the importance of integrating archaeological evidence with climate data to achieve a comprehensive understanding of historical human adaptations.

The results hold significant implications for understanding past climate and human interaction within Australia. They illustrate how the climatic conditions dictated by the monsoonal activity could either bolster or hinder the stability of human populations. For instance, the data revealed that the Murray-Darling Basin saw a notable decrease in precipitation of approximately 18% during this period, reinforcing the idea of an inhospitable environment that may have prompted Aboriginal communities to retreat to more favorable locations.

As researchers continue to refine climate models, the goal is to provide clearer connections between paleoclimate data and the patterns of human settlement. Understanding the climate faced by early inhabitants helps us unravel the story of human resilience and adaptation in the face of pronounced environmental change. “To understand the climate faced by early populations of Sahul, particularly during a period of known expansion into previously marginal landscapes, accurate quantification of the palaeoclimate is significantly improved when using finer resolution climate models,” the authors concluded.

This latest research is not just a step forward in deciphering Australia's climatic past; it sets the groundwork for future studies that seek to combine climate modeling with archaeological findings, offering a more integrated approach to studying human history on the continent. Moving forward, the research not only aims to understand past climatic events but also to draw parallels with modern climate changes, ensuring that the lessons of history inform current environmental policies and human adaptability.