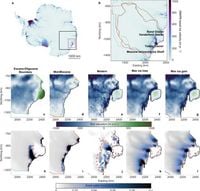

Researchers studying the Aurora Subglacial Basin (ASB) in East Antarctica have developed a comprehensive model of the region's changing subglacial drainage systems over the last 34 million years. This pioneering work reveals crucial insights into how these evolving water flows could lead to accelerated ice loss, with significant implications for global sea levels as climate change progresses.

The ASB has been identified as one of the most rapidly changing regions in Antarctica, particularly in relation to the Totten Glacier, which exhibits alarming rates of ice thinning and discharge. This glacier is a significant contributor to sea level rise, with the East Antarctic Ice Sheet containing the potential for a staggering 52 meters of rise if all the ice were to melt. The urgency of this research underscores the need to understand the mechanisms driving these changes, especially as models predict future instability in this critical region.

The research employs a two-dimensional finite-element model known as the Glacier Drainage System (GlaDS) to assess how the geometry of ice sheets and subglacial hydrology influence one another. The authors meticulously examined past and projected future configurations of ice, simulating various scenarios to understand the mechanisms of mass loss. They found that subglacial drainage could account for up to 70% of the melt occurring at the base of the floating ice shelves in the ASB, calling into attention its pivotal role in driving ice dynamics.

Notably, the researchers observed that the past does not fully serve as an analogue for the future. Previous models have often overlooked the critical impact of evolving subglacial drainage systems, which can trigger more significant rates of mass loss than previously anticipated. By ignoring the complexities of subglacial hydrology, projections may significantly underestimate future responses of Antarctic ice sheets to climate warming.

In their findings, the researchers indicated that the ASB's drainage systems underwent continual reorganization, reflecting a dynamic response to changing ice-sheet configurations and greenhouse gas concentrations. At the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary, for example, the model showed that channels were significantly longer than those observed today, drastically increasing water discharge rates at the grounding lines.

As the model progressed toward projected conditions for 2100, it highlighted the potential for fundamentally different subglacial hydrological systems, particularly under high emissions scenarios. Scenarios with maximum ice loss indicated that channel lengths and discharges could be twice that of present-day configurations. This suggests a reorganization of drainage networks that could fundamentally alter how ice interacts with the ocean, potentially leading to heightened melt rates at ice shelf bases.

Furthermore, the research sheds light on the interaction between warm ocean water and grounded glaciers, with climate change potentially facilitating the intrusion of warmer, modified Circumpolar Deep Water into glacial regions. This interaction could exacerbate the erosion of ice shelves, a process that has already been implicated in the observed grounding line retreats and heightened discharge rates of the Totten Glacier.

The significance of this work extends beyond mere academic inquiry; understanding how subglacial dynamics influence ice loss will ultimately contribute to more accurate predictions of sea level rise in the coming decades. With rising global temperatures, the stakes are high, and the research delivers powerful insights into the mechanisms that could push the Antarctic ice sheets beyond critical thresholds.

Moreover, previous studies suggest that periods of historical climate warmth may provide insights into possible future conditions, yet the findings challenge the assumption that past climate analogues can directly translate to future scenarios. Researchers stress that while certain similarities exist—such as volume and flow characteristics—the ways in which these past systems functioned differ fundamentally from those projected in a warming climate.

In light of these findings, the researchers call for further studies that incorporate the intricate relationships between past and contemporary subglacial hydrology and ice dynamics. They encourage future research to integrate evolving hydrological models with ice sheet dynamics, which is paramount for enhancing the accuracy of predictions concerning future sea-level contributions from Antarctica.

This groundbreaking work not only contributes to our understanding of past glacial dynamics but also emphasizes the urgent need for refined models that can capture the complexities of the mechanisms driving ice loss. As climate change continues to unfold, the revelations from the ASB research will serve as a critical juncture for scientists aiming to protect coastal communities and ecosystems vulnerable to rising sea levels.

In conclusion, the Aurora Subglacial Basin research presents a vital piece in the puzzle of understanding Antarctic ice dynamics and its implications for global sea-level rise. The modeled shifts in subglacial drainage and ice shelf melting reveal a manipulation of ice flow that resonates with the urgent need for action to mitigate the impacts of climate change.