A new study highlights the considerable impact of historic nitrogen fertilization on nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils, revealing that common methods for estimating emissions have significantly underestimated their potential impact on climate change.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is not only a potent greenhouse gas, with a global warming potential approximately 300 times greater than that of carbon dioxide, but it also plays a major role in stratospheric ozone depletion. Agricultural practices, particularly the use of nitrogen fertilizers, are responsible for approximately 52% of global anthropogenic N2O emissions. This figure has been rising, with direct emissions from agriculture increasing from 1.5 Tg N yr−1 in the 1980s to 2.3 Tg N yr−1 during 2007–2016. With nitrogen fertilizer use projected to grow even further—from 81 Tg N yr−1 in 2000 to 113 Tg N yr−1 in 2020—the urgency to address these emissions has never been clearer.

Traditionally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has relied on short-term measurements to establish emission factors (EFs) for agricultural soils. These are crucial for estimating how much of the applied nitrogen is emitted as nitrous oxide. However, the latest research suggests that these estimates are significantly flawed.

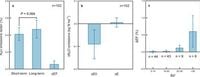

The researchers compiled and synthesized data from numerous field experiments to assess whether the duration of nitrogen application affects nitrous oxide emissions. Their findings indicate that EFs are systematically underestimated when relying solely on short-term studies, which typically last only 1 to 3 years.

One of the striking outcomes from their analysis showed that EFs increase over the long-term as soils receive continual nitrogen fertilization. Specifically, historical fertilization significantly positively correlates with current N2O emissions due to heightened nitrogen availability and reduced soil pH. These factors foster a surge in nitrous oxide-producing microorganisms, leading to increased emissions from fields that had stopped receiving nitrogen input compared to those that had not been fertilized for long periods.

The new estimations suggest that global EFs for cropland should be revised to about 1.9%, with annual fertilizer-induced N2O emissions potentially reaching 2.1 Tg N2O-N per year. This represents a staggering increase of around 110% from past IPCC estimates.

Furthermore, the team's investigation included incubation experiments, where they observed that soils from fields that had recently experienced nitrogen application emitted 36% to 52% more nitrous oxide compared with long-term zero-nitrogen application soils for crops like wheat, maize, and rice.

"Our findings highlight the significance of legacy effects on N2O emissions, emphasize the importance of long-term experiments for accurate N2O emission estimates, and underscore the need for mitigation practices to reduce N2O emissions", wrote the authors. This powerful statement encapsulates the study's implications, suggesting that the agricultural sector needs to reevaluate its practices regarding nitrogen application to effectively combat climate change.

A deeper dive into soil properties revealed trends consistent with the emissions data. With ongoing nitrogen input, soil total nitrogen contents and extractable nitrogen concentrations surged. In contrast, soil pH declined, which is another contributing factor to elevating nitrous oxide emissions.

The authors call for a broader adoption of sustainable agricultural practices to mitigate the environmental consequences of nitrogen fertilization. Enhanced-efficiency nitrogen fertilizers, improved crop varieties with higher nitrogen utilization, and reduced nitrogen surpluses are among the strategies presented that can cut N2O emissions by up to 30% without sacrificing crop yields.

In conclusion, this study represents a turning point in how we understand the global impact of agricultural nitrogen fertilization on greenhouse gas emissions. As systems of global food production continue to evolve, integrating these findings into nitrogen management strategies will be crucial for agriculture’s role in battling climate change.