In 1961, amid the chaos following the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, President John F. Kennedy found himself at odds with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The aftermath of the invasion, which took place on April 17, 1961, saw Kennedy lashing out at the agency’s leadership, particularly targeting CIA Director Allen Dulles and his deputy for covert operations, Richard Bissell. Kennedy believed they were directly responsible for the disastrous military mission that had unfolded.

The Bay of Pigs invasion was intended to overthrow Fidel Castro's regime in Cuba but ended in failure, leading to a significant embarrassment for the U.S. government. Frustrated by the lack of accountability and the intelligence failures that had led to the invasion, Kennedy expressed a desire to dismantle the CIA, famously threatening to "scatter the CIA in a thousand pieces and scatter it to the winds." This sentiment was captured in newly declassified documents that provide insight into Kennedy's frustrations with the agency.

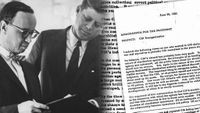

Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive, highlighted the importance of these documents, which reveal the depth of Kennedy's concerns about the CIA's operations. In May 1961, following the Bay of Pigs disaster, Kennedy had requested a memorandum from historian and advisor Arthur Schlesinger Jr. regarding the organization of British intelligence services. He aimed to understand how these operations could inform a potential reorganization of the CIA.

Schlesinger’s memorandum compared the operational structure of British intelligence, particularly MI6, to that of the CIA. He emphasized the importance of maintaining political oversight over intelligence operations, advising Kennedy that the British approach allowed for a separation between information collection and covert operations. Schlesinger warned that the CIA's lack of accountability had led to significant political failures, including the debacle in Cuba.

In his analysis, Schlesinger pointed out that the CIA's "lack of accountability" had allowed for inappropriate political initiatives and suggested that the agency's operations should be more coordinated with the State Department. He argued that the CIA's autonomy had effectively turned it into a "state within a state," operating independently of U.S. foreign policy.

In June 1961, Schlesinger submitted a second memorandum to Kennedy, detailing a comprehensive plan for the reorganization of the CIA. This document, which has now been fully declassified, outlined the agency's core functions, including intelligence collection, covert political operations, and paramilitary activities. Schlesinger criticized the CIA's unchecked power and proposed that its operations be restructured under the State Department, echoing the British model of intelligence management.

Despite Schlesinger's warnings, Kennedy ultimately ignored the advice, and the agency continued its operations without significant oversight. Kornbluh speculated that had Kennedy heeded Schlesinger's recommendations, the CIA's legacy might not have been marred by scandals such as the Mongoose operation, the overthrow of democratically elected governments, and the Iran-Contra affair.

As the Cold War intensified, the CIA's activities became increasingly controversial. Among the most notorious programs was MK-Ultra, a secret CIA initiative aimed at exploring mind control techniques. Officially launched in 1953 under the direction of Allen Dulles, MK-Ultra sought to develop methods for controlling human behavior, decision-making, and memory.

Funded secretly and conducted in various academic institutions, psychiatric hospitals, and military bases, MK-Ultra involved the use of drugs such as LSD and scopolamine on unwitting subjects, including homeless individuals, prisoners, and even American soldiers. The ultimate goal was to create individuals who could be manipulated without their knowledge, effectively turning them into spies or operatives.

One of the most infamous incidents associated with MK-Ultra was the case of Frank Olson, a biochemist who worked for the CIA. Olson was given LSD without his consent during an experiment, leading to his mysterious death shortly after. Initially ruled a suicide, subsequent investigations revealed that Olson may have been pushed from a hotel window, raising questions about the ethics of the CIA's experiments.

The MK-Ultra program was officially terminated in 1973, but details of its operations remained largely hidden from the public. In the years that followed, some documents were inadvertently released, shedding light on the extent of the program's reach and the ethical violations that occurred. Congressional hearings in the mid-1970s revealed shocking details, but much of the evidence had been destroyed, leaving many questions unanswered.

As the CIA's controversial history continues to unfold, the legacy of its operations during the Cold War remains a subject of intense scrutiny. The agency's role in covert operations, both domestically and internationally, has raised ethical concerns that resonate to this day. The revelations surrounding Kennedy's frustrations with the CIA and the subsequent fallout from programs like MK-Ultra serve as a stark reminder of the complexities and moral ambiguities inherent in intelligence work.

In hindsight, the events of the early 1960s marked a turning point in the relationship between the U.S. government and its intelligence agencies. Kennedy's push for reform and accountability within the CIA reflected a growing recognition of the need for oversight in an era where secrecy and covert operations could have profound implications for both national security and civil liberties.

As historians and analysts continue to examine this tumultuous period, the lessons learned from Kennedy's tenure and the CIA's controversial programs will undoubtedly shape discussions about intelligence, ethics, and governance for years to come.