In the winding streets of Srinagar, bookshop owners watched anxiously as police officers combed through their shelves, searching for volumes now deemed forbidden. On August 7, 2025, authorities in Indian-administered Kashmir launched a sweeping crackdown, raiding bookstores and roadside vendors to confiscate 25 books that had been banned just days earlier. The government accused these works—penned by a mix of Indian and international authors—of promoting “false narratives” and “secessionism,” a move that has since drawn sharp criticism from writers, academics, and defenders of free speech across the globe.

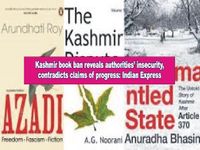

The list of banned titles reads like a roll call of acclaimed scholarship and literary achievement. Among those targeted are Arundhati Roy, winner of the Booker Prize; constitutional expert AG Noorani; historians Sumantra Bose, Christopher Snedden, and Victoria Schofield; and journalist Anuradha Bhasin. Even Hafsa Kanjwal’s award-winning Colonizing Kashmir: State-Building under Indian Occupation was included, despite having just received the Bernard Cohn Book Prize for outstanding South Asian scholarship. The government’s order, issued under India’s new 2023 criminal code, makes possession or sale of these books a criminal offense, punishable by prison terms. This is not just a symbolic gesture—police have actively enforced the ban, seizing books from shops, roadside stalls, and even private homes.

According to police statements cited by Al Jazeera, “The operation targeted content that promotes secessionist ideologies or glorifies terrorism. We urge public cooperation to maintain peace and integrity.” The government claims these books “misguide youth” and instigate violence, alleging that the literature “would deeply impact the psyche of youth by promoting a culture of grievance, victimhood, and terrorist heroism.”

Yet, as critics are quick to point out, many of these banned works have been in circulation for decades, widely respected for their nuanced explorations of Kashmir’s history and the region’s long-standing disputes. Victoria Schofield, whose own book Kashmir in Conflict was proscribed, questioned the government’s motives in an article published by The Wire on August 9, 2025. “None of these books or the others on the proscribed list promote, as has been alleged, ‘a culture of grievance, victimhood and terrorist heroism,’” she wrote. “They merely elucidate why it may have developed.” Schofield added, “It does not distort history, it provides an account through multiple voices of why the dispute arose, why it has not been resolved and why, to achieve peace and stability in the region, dialogue among the protagonists is essential.”

This latest ban coincides with the sixth anniversary of the abrogation of Article 370, the constitutional provision that had granted Jammu and Kashmir a degree of autonomy within India. Since the revocation of that status in 2019, the Indian government has steadily tightened restrictions on dissent in the region, clamping down not only on political opposition but also on media, academia, and now, literature. The timing of the ban has left many observers baffled, especially given the government’s repeated claims that normalcy and development are returning to the valley. As Schofield noted, “What has made the Indian government so insecure that its attention has been drawn to these books now rather than even in the height of insurgency against the Indian government in the valley of Kashmir in the 1990s, or at any other time since?”

The editorial board of Indian Express was similarly critical, arguing in an August 9, 2025, editorial that the ban reveals “a deepening insecurity within the territory’s administration” and contradicts claims of progress under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government. The editorial pointedly asked, “What changed between March and August that an establishment which was congratulating itself for the progress made in Kashmir should display such heightened insecurity five months later that it should seek to banish books?” The piece went on to argue that censorship and repression only fuel alienation and distrust, rather than promoting unity or lasting peace. “The ban on books is both disturbing and disheartening,” the editorial concluded, stressing that open engagement with diverse narratives is essential for any hope of reconciliation.

For many Kashmiris, the book ban is only the latest in a long history of censorship and information control. Hafsa Kanjwal told Al Jazeera, “Nothing is surprising about this ban, which comes at a moment when the level of censorship and surveillance in Kashmir since 2019 has reached absurd heights.” She also pointed out the irony: even as the authorities raided bookstores, the Indian army was promoting a state-sponsored Chinar Book Festival on the banks of Dal Lake in Srinagar. “It is, of course, even more absurd that this ban comes at a time when the Indian army is simultaneously promoting book reading and literature,” Kanjwal remarked.

Veteran editor Anuradha Bhasin, whose book A Dismantled State: The Untold Story of Kashmir After Article 370 was also banned, described the accusations against her work as “strange.” She told Al Jazeera, “Nowhere does my book glorify terrorism, but it does criticise the state. There’s a distinction between the two that authorities in Kashmir want to blur. That’s a very dangerous trend.” Bhasin warned that such bans will have far-reaching implications for future scholarship on Kashmir, as publishers may grow increasingly reluctant to print anything critical of the government’s actions in the region.

The ban’s impact on academic freedom and historical memory is already being felt. Sabir Rashid, a 27-year-old independent scholar from Kashmir, lamented, “If we take these books out of Kashmir’s literary canon, we are left with nothing.” Rashid, who is working on a book about Kashmir’s modern history, fears that his research will now be “naturally going to be lopsided.” He added, “These books served as sentinels. They were supposed to remind us of our history. But now, the erasure of memory in Kashmir is nearly complete.”

For historian Sumantra Bose, whose book Kashmir at the Crossroads was also banned, the government’s actions are both personal and historical. Bose noted, “Ninety years later, I have been accorded the singular honour of following in the legendary freedom fighter’s footsteps,” referring to his great-uncle Subhas Chandra Bose, whose own writings were banned by colonial authorities in 1935. The move, he suggested, is part of a broader pattern of suppressing dissenting voices in the name of national security.

Globally, book bans have rarely succeeded in quelling unrest or fostering reconciliation. As the Indian Express editorial observed, “Across the world, in societies moving towards a resolution of tangled histories, repressive acts like book bans have rarely contributed to lasting accommodation, or assimilation. By all accounts, the most effective tool to bring stability and combat disenchantment remains a deepening of democracy and institutionalisation of people’s participation in decision-making.”

For now, the shelves in many Srinagar bookshops sit a little emptier, and the region’s literary community is left to wonder what stories will be lost to the next generation. The debate over Kashmir’s future continues, but, as history shows, the urge to silence dissenting voices rarely brings the peace it promises.