For over 136 years, the identity of Jack the Ripper—the notorious serial killer who terrorized London's Whitechapel district—has remained one of history's most haunting mysteries. Now, thanks to groundbreaking DNA analysis and advanced facial reconstruction techniques, some researchers believe they have finally unveiled the face of this infamous figure, positing Aaron Kosminski, a Polish immigrant and previous suspect, as the likely murderer.

Russell Edwards, who has devoted nearly three decades to unraveling the enigma of Jack the Ripper, claims this new evidence not only confirms Kosminski's identity but also sheds light on the bizarre brutality of the murders and the reason behind them. This latest development builds on Edwards’ earlier findings, using forensic analysis from a shawl retrieved from the crime scene of one of the victims, Catherine Eddowes.

The shawl, recovered by police officer Amos Simpson after Eddowes' gruesome murder on September 30, 1888, remained within the Simpson family for generations before it came to auction. Edwards purchased it at auction, and initial investigations revealed it contained blood and bodily fluid stains. Subsequent DNA testing indicated these stains matched those of both Eddowes and Kosminski's descendants, strengthening Edwards' claims.

During the span known as the Canonical Five murders—from August to November 1888—five women were brutally killed, their bodies left mutilated with deliberate precision. The victims, including Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, and Mary Jane Kelly, were all attacked under similar circumstances, their throats slashed and organs removed, indicating the killer had some degree of anatomical knowledge.

The broader investigation, known as the Whitechapel murders, included casualties from April 1888 up until February 1891, encompassing at least 11 women, the majority from impoverished backgrounds. The reach of the investigation brought considerable attention to Kosminski as well as to societal views on the victims, often reduced to mere statistics without acknowledgment of their humanity.

Edwards notes the exceptional nature of the shawl's origins. It bore elaborate floral designs and dyes thought to be inconsistent with Eddowes' impoverished status. The questions sparked by its design led Edwards to suspect it could belong to Kosminski, who emigrated from the Russian Empire. Through DNA matching, the evidence suggested the presence of Kosminski’s lineage at the crime scene.

Interestingly, Edwards links Kosminski's potential connections to the Freemason community to his evasion of police capture. Historical records suggest his brother, Isaac Kosminski, was involved with freemasonry, which Edwards theorizes could have protected the family during the investigation, preventing harsher scrutiny because of the prejudices faced by Jewish immigrants at the time. This posits the Freemason connection as significant, acting as both possible shield and motive.

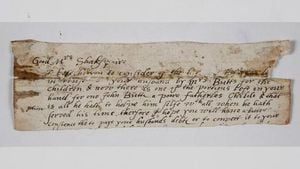

Further adding tension to this narrative is the ambiguous message left at one of the murder scenes, bearing the phrase “The Juwes are not to be blamed for nothing.” This phrase, believed to reference Masonic terminology, has fueled speculation of Masonic involvement or at least awareness, adding layers of intrigue to Edwards’ findings.

Another disturbing aspect of these claims surrounds the gruesome nature of the murders. Edwards posits theories connecting the method of the killings to ancient Masonic rituals, which prescribe certain symbolic cuttings—throat slitting, for example—as acts of revenge or illustrating secrecy. This interpretation could allow for the conclusion of motive intertwined with his brother's associations and the societal backdrop under which these crimes occurred.

The reconstructed likeness of Kosminski—produced by feeding images of his living relatives through facial reconstruction software—offers the world its first glimpse of the man believed by Edwards to be Jack the Ripper. This computer-generated image shows a young man with high cheekbones and dark features, characteristics seemingly fitting the suspected criminal. Edwards’ emphasis on the visual identity of Kosminski aims to solidify the narrative, moving beyond speculation to establish his character within this infamous historical narrative.

Despite these advancements, controversies and debates remain. Critics of Edwards' claims point to the historic hesitance to label Kosminski as the murderer due to fears over anti-Semitism—a concern rooted deeply within the political climate of Victorian England. This nuanced crossroads of race, fear, and brutal crime complicates the tale of Jack the Ripper, and Edwards suggests many officials were deterred from focusing on Kosminski due to potential backlash.

After years of research, the lid appears to be cracking on one of fiction's greatest real-life mysteries. The findings authored by Russell Edwards, especially his latest book, Naming Jack The Ripper: The Definitive Reveal, promise to captivate audiences yet again as they traverse through the intersecting paths of folklore, forensic evidence, and historical truths. The closure of this long-pondered case, if validated, would mark a chilling milestone not only for historians and detectives but for society's grasp on the legacy of crime and punishment across time, sparking renewed discussions about societal issues much prevalent today.

With Kosminski characterized as the Ripper, the infamous allure of Jack the Ripper as one of the world's first media-hyped serial killers continues to draw interest, debate, and even horror, forever impacting public perception of true crime narratives. The continuing saga of the Whitechapel murders demonstrates how history casts long shadows, propelling young researchers and veteran investigators alike to seek clarity within chaos, fostering both admiration and skepticism as the layers of this dramatic case are peeled away.