On August 24 and 25, 2025, a rare moment of cross-border communication unfolded between India and Pakistan, as Indian authorities reached out to warn their neighbor of impending flood risks. This gesture, made in the midst of frayed diplomatic ties and a suspended Indus Waters Treaty, has cast a spotlight on the delicate intersection of politics, climate crises, and humanitarian necessity in South Asia.

The notification came as the Indian High Commission in Islamabad formally alerted Pakistani officials of increased water flow into the Sutlej River, and earlier, a high flood level in the Tawi River at Jammu—a tributary that eventually crosses into Pakistan’s Gujrat and Sialkot districts. According to Dunya News, this was only the second official contact since the May 2025 military conflict, and, notably, the first significant exchange of flood-related information since then. The alert, delivered at 10:00 a.m. on August 24, was followed by Pakistan’s Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) issuing a flood warning, directing local administrations to activate monitoring systems and prepare early response measures.

But the context of this communication was far from routine. As Reuters reported, India’s warning was delivered “on humanitarian grounds,” explicitly not under the terms of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT)—a landmark 1960 agreement brokered by the World Bank that has long divided the rivers of the Indus basin between the two nuclear-armed rivals. India had declared the treaty in “abeyance” this April, following a deadly attack on Hindu tourists in Kashmir, which it linked to Pakistan. The move marked a dramatic escalation in tensions, coming on the heels of what Reuters described as the “worst military clash between the nuclear-armed rivals in decades.”

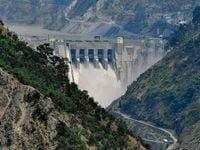

For decades, the IWT has been a rare thread of cooperation, surviving three wars and numerous standoffs. The treaty allocates three eastern-flowing rivers to India and three westward rivers to Pakistan, with the latter relying on the Indus basin to irrigate nearly 80% of its farmland. The stakes are high: any disruption to these flows, Pakistani officials warn, could endanger the country’s food security and hydro-power, and, in their words, would be considered “an act of war.”

Yet, as the monsoon season has battered the region, the need for timely flood data has become a matter of life and death. In August alone, flash floods across northern Pakistan, Kashmir, and India have killed at least 321 people, according to reporting by Ashraf Patel of the Institute for Global Dialogue. In Pakistan, the situation is especially dire: since late June, monsoon rains, flash floods, and landslides have claimed nearly 800 lives, with thousands displaced, crops destroyed on thousands of acres, and rising losses of livestock. The devastation has been compounded by India’s recent release of water from the Harike Headworks into the Sutlej River, which, as Dunya News detailed, has already displaced thousands in Pakistan and threatened livelihoods downstream.

Amid these natural disasters, the political temperature has only risen. On August 15, both countries marked their Independence Days with pointed rhetoric. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, speaking from Delhi’s historic Red Fort, declared a “new normal” in which India would no longer tolerate “nuclear blackmail” from Islamabad. "For a long time, nuclear blackmail had been going on, but this blackmail will not be tolerated now," Modi said, as quoted by BBC. Across the border, Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif announced the creation of a new “Army Rocket Force Command,” underscoring the ongoing arms race and military posturing that have come to define the bilateral relationship.

But as Patel points out in his analysis, these displays of military might mask deeper, more pressing crises. Both India and Pakistan are grappling with what he calls a “polycrisis”—a convergence of economic, social, and environmental challenges that threaten the well-being of their citizens. The scars of the 1947 partition, the legacy of hyper-nationalism, and the siphoning of national budgets into defense spending have left ordinary people vulnerable and underserved. “Self-serving elites, corrupt politicians, a crass nationalist media, and the military establishment in both societies have siphoned off national budgets away from real development,” Patel writes.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the countries’ responses to climate change. The current floods and recent droughts are stark reminders that environmental disasters recognize no borders, race, religion, or language. Yet, cooperation remains elusive. Experts warn that, despite the suspension of the IWT, the sharing of flood data—even when relations are strained—could prove vital in minimizing the toll on vulnerable downstream communities. As one expert noted, “timely sharing of flood data, even under strained relations, could prove vital in minimising the human and agricultural toll.”

Social and economic challenges further complicate the picture. Both countries face severe unemployment, especially among youth. According to a March report from the International Labor Organization, “the youth unemployment rate has increased with the level of education, with the highest rates among those with a graduate degree or higher and higher among women than men.” In Pakistan, youth joblessness is particularly alarming, with 44.9% of jobseekers aged 15–24, and female unemployment far exceeding male, as reported by Dawn. These issues are compounded by gender-based violence and deep-seated inequalities, with women and marginalized groups bearing the brunt of corporate abuse, labor exploitation, and limited access to justice, as highlighted by Action Aid India.

Patel and other analysts argue that a new narrative is urgently needed—one rooted in objective reality and focused on cooperation, not confrontation. They suggest that if both nations reduced defense spending by just 15%, billions could be unlocked for social development, climate adaptation, and job creation. “The vast majority of citizens are exhausted of conflict and war talk, knowing the dire social costs,” Patel observes. “Their focus is on bread-and-butter issues—jobs and a better life for aspirational youth.”

There are glimmers of hope. Diaspora communities, civil society dialogues, and people-to-people exchanges could help foster understanding and push leaders toward more constructive engagement. The United Nations’ Pact of the Future 2024 and forums like BRICS and the G77 offer frameworks for regional cooperation, even as the world grows more fragmented and aid flows from the West diminish.

Still, the road ahead is fraught. Both India and Pakistan remain outside the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and human rights abuses and authoritarian tendencies are on the rise in both societies. Yet, the urgency of the climate crisis, and the shared vulnerability of ordinary citizens, may yet force a reckoning. As Patel concludes, “A new narrative is required for these two Asian nations in a Polycrisis world.”

Whether the recent flood warnings mark the beginning of a new chapter of pragmatic cooperation, or simply a brief pause in a long history of rivalry, remains to be seen. For now, the rivers keep flowing—and the lives of millions depend on what happens next.