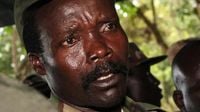

In a historic move that underscores both the persistence of international justice and the profound challenges it faces, the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague has opened a three-day confirmation of charges hearing against Joseph Kony, the elusive Ugandan warlord and founder of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The proceedings, which began on September 9, 2025, mark the first time the tribunal has advanced a case of this magnitude without the accused present in court—a precedent that could shape the future of international law.

Kony, now infamous worldwide for his reign of terror across northern Uganda and neighboring countries, has been on the ICC’s wanted list since 2005. Despite nearly two decades of international pursuit—spanning Interpol red notices, African Union missions, and even U.S. military advisers—he remains at large. The court’s decision to move forward in his absence reflects both the urgency of delivering justice to victims and the frustration of years spent chasing a fugitive who has managed to evade every net cast for him.

The list of charges against Kony is both extensive and harrowing. He faces 39 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, enslavement, torture, sexual slavery, forced pregnancy, and the use of child soldiers. According to CourtHouse News, one count alone holds him responsible for the deaths of more than 600 civilians in camps across northern Uganda. Prosecutors allege Kony not only orchestrated abductions but also directed systematic assaults on schools and camps for displaced families, overseeing a regime of forced marriages and sexual violence from July 2002 until December 2005.

In opening statements, ICC deputy prosecutor Mame Mandiaye Niang did not mince words: “The social and cultural fabric of Northern Uganda has been torn apart and it is still struggling to rebuild itself.” Niang emphasized that the scars of the LRA’s violence remain visible, with victims “still scarred in their body and spirit,” as reported by Associated Press (AP).

The hearing is not a trial, but rather a critical checkpoint in the ICC’s process. Prosecutors are presenting their evidence before a panel of three judges, who must decide whether the case against Kony is strong enough to confirm the charges and prepare for a full trial—should he ever be apprehended. As CourtHouse News explains, “This case is the first at the International Criminal Court where the confirmation proceedings and hearings are held in absentia.” However, any eventual trial will require Kony to be physically present in court, in keeping with ICC rules.

The prosecution’s case has been both graphic and deeply personal. In one particularly haunting account, a protected witness recalled, “I saw children younger than me being trained to shoot with weapons. I knew they were so young because the muzzles of their AK-47 rifles dragged on the ground when they carried them on their shoulders.” Prosecutors described how girls and young women were enslaved and subjected to forced pregnancies, while boys were forced to become child soldiers—a vicious cycle that turned many victims into perpetrators themselves.

Kony’s LRA first emerged in the late 1980s, rooted in a spiritualist movement in northern Uganda before transforming into a brutal insurgency. Over the years, the group’s fighters have crossed borders into the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, and South Sudan, making efforts to capture Kony extraordinarily difficult. The ICC’s hearing revisited the Ugandan government’s 2002 “Operation Iron Fist,” a massive military campaign that destroyed LRA camps in Sudan but failed to capture its leader. Instead, the group scattered, and Kony slipped further into obscurity.

The human toll of the conflict is staggering. By the early 2000s, more than a million people had been displaced from their homes in northern Uganda, as reported by CourtHouse News. International outrage swelled, leading Kampala to refer the situation to the newly formed ICC in 2004—the court’s first-ever state referral. A year later, arrest warrants were issued for Kony and four of his top commanders, marking the ICC’s first public cases.

Of the original group of wanted LRA leaders, three have since been confirmed dead. Dominic Ongwen, who was himself abducted by the militia as a child and later became a brutal commander, was tried and convicted by the ICC in 2020 for 61 offenses, including murder, rape, forced marriage, and recruiting child soldiers. Ongwen is currently serving a 25-year sentence in Norway. Kony, meanwhile, remains the only fugitive, his whereabouts unknown despite a $5 million reward and years of pursuit by U.S. special forces, as highlighted by AP.

The decision to proceed with charges in Kony’s absence has not been universally welcomed. Court-appointed counsel for Kony, Peter Haynes, argued that the proceedings violate his client’s fair trial rights, stating, “The empty chair impacted the preparation of the defense,” according to AP. Some Ugandans, too, have expressed skepticism about the value of a hearing without the accused. Odonga Otto, a former lawmaker from northern Uganda, told AP, “Why do you want to try a man you can’t get? They should first get him. It’s a mockery.” Others, like survivor Odong Kajumba, see the hearing as a long-awaited measure of justice: “He did many things bad. If they can arrest Kony, I am very happy.”

Legal experts are watching closely, noting that the ICC’s move could set a precedent for other high-profile cases where suspects are unlikely to be detained. Michael Scharf, an international law professor at Case Western Reserve University, told AP, “Everything that happens at the ICC is precedent for the next case.” He pointed out that while the whereabouts of other ICC suspects—such as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Russian President Vladimir Putin—are known, Kony has managed to vanish entirely.

Kony’s notoriety reached a global peak in 2012, when a viral video brought his crimes to the world’s attention. But despite international campaigns and relentless pursuit, he remains at large. The ICC’s decision to move forward is in part a message to survivors that their suffering has not been forgotten. As the prosecution put it, “Many victims who had the strength to survive the horrors of a devastating civil war have unfortunately not survived this lengthy wait. Others have lost patience. But there are still those who, against all odds, have waited for this very moment.”

The hearing continues, with prosecutors set to present further evidence before victims’ representatives and Kony’s defense team have their turn. Once the three-day session concludes, it will be up to the judges to decide if the evidence is solid enough to confirm the charges. Should they do so, a trial chamber will be established—waiting for the day Joseph Kony is finally brought to justice in The Hague.

The ICC’s bold step this week is both a testament to the enduring hope for accountability and a sober reminder of the obstacles that remain in the pursuit of global justice.