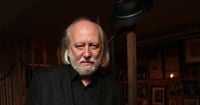

László Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian novelist once described by Susan Sontag as a "master of the apocalypse," has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, marking a triumphant moment for Hungarian letters and for a writer whose work has long thrived on the very edge of international literary consciousness. The Swedish Academy’s announcement on October 9, 2025, lauded Krasznahorkai for his "compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art." For readers, writers, and critics across the globe, the recognition is both a celebration and an invitation: to discover, or perhaps finally confront, the dense, enigmatic worlds Krasznahorkai has spent decades constructing.

Krasznahorkai’s rise to literary prominence in the West has been anything but straightforward. As Andrew Ervin recounted in his Philadelphia City Paper review from January 2001—believed to be the first American write-up of Krasznahorkai’s work—the author’s English-language debut, The Melancholy of Resistance, arrived in the United States with little fanfare but immense promise. Ervin’s review, now resurfacing in light of the Nobel, is a testament to the slow-burning influence of Krasznahorkai’s fiction. "The publication of László Krasznahorkai’s The Melancholy of Resistance can change all that. It’s one Hungarian book well deserving of a place on every reading list and within every new year’s resolution," Ervin wrote at the time.

Born in 1954 in the small town of Gyula, Hungary, Krasznahorkai’s early life was marked by secrecy and artistic ambition. His family’s Jewish roots were hidden—his grandfather changed their name from Korin to Krasznahorkai to assimilate—and he only learned of his heritage at age eleven. A musical prodigy, he played piano in a jazz band and sang in a rock group before turning to literature. His path was anything but linear: after studying Hungarian language and literature, he deserted the Hungarian army following a punishment for insubordination, and later worked as a miner and a night watchman, jobs that gave him time to read Dostoyevsky and Malcolm Lowry.

Krasznahorkai’s literary career began under the shadow of Hungary’s Communist regime, a period of censorship and surveillance. His debut novel, Satantango (1985), was a subversive sensation in Hungary—a bleak, sprawling tale set on a decaying collectivist farm, filled with paranoia and confusion. "Nobody, myself included, could understand how it was possible to publish Satantango because it’s anything but an unproblematic novel for the Communist system," Krasznahorkai later reflected in a 2018 Paris Review interview. The novel’s adaptation into a seven-hour film by Béla Tarr in 1994 cemented its cult status.

If Satantango was Krasznahorkai’s explosive debut, The Melancholy of Resistance (originally published in 1989) confirmed his reputation for relentless prose and philosophical depth. The novel, set in a small rural village near the Hungarian-Romanian border during the waning years of Russian occupation, revolves around the arrival of a traveling circus bearing the remains of the largest whale in the world—a blank metaphor onto which readers project their own anxieties. Ervin observed, "The enormous dead beast being dragged from city to city serves as a blank metaphor. The author leaves the story open-ended enough that every reader can apply his or her own interpretation."

Krasznahorkai’s style is unmistakable: vast, winding sentences that can run on for pages, paragraphs that resist abbreviation or quotation, and a narrative voice that shifts without warning. The translation by George Szirtes has been widely praised for maintaining the original’s momentum and rich language. Szirtes himself has remarked, "The books can look daunting in some ways, simply because there is no break in them." Yet within this density, Barbara Epler of New Directions highlights, lies "an escalating, incredibly deadpan hilarity."

Despite—or perhaps because of—his formidable style, Krasznahorkai has attracted a devoted following among writers and critics. He has written half a dozen screenplays with Béla Tarr, who adapted The Melancholy of Resistance into the 2000 film Werckmeister Harmonies. His latest novel to appear in English, Herscht 07769, published in the United States in 2024, unfolds in a single sentence and explores the rise of fascism in Europe through the eyes of a graffiti cleaner in Germany.

Krasznahorkai’s relationship with politics is complex. While his work often contains critiques of authoritarianism and the rise of right-wing ideology, he has consistently rejected the label of political novelist. "I never want to write some political novels," he told The New York Times in 2014. "My resistance against the Communist regime was not political. It was against a society." Still, as translator Ottilie Mulzet notes, "He holds up this mirror of satire to Hungarian society. He’s been very courageous in making his stance known that he’s not really pleased with Orbán." This is no small feat in contemporary Hungary, where dissenting voices can face harassment. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, for his part, congratulated Krasznahorkai on social media, saying he "brings pride to our nation."

International recognition has followed slowly but steadily. Krasznahorkai won the Man Booker International Prize in 2015 for his entire body of work, and New Directions has published a dozen of his books in translation, with more on the way. His influence has seeped into the literary mainstream—James Wood’s 2011 essay in The New Yorker is often cited as the moment the "Krasznahorkai Era" dawned in America. Yet for years, his books were the province of the adventurous reader, their reputation for difficulty both a barrier and a badge of honor.

Andrew Ervin’s personal connection to Hungarian literature began in the 1990s, when he lived in Budapest and contributed to English-language newspapers. He later met Krasznahorkai at the Brooklyn Book Festival in 2015, where the author signed a copy of Seiobo There Below for Ervin and his wife (albeit, amusingly, misspelling her name). Ervin’s early review of The Melancholy of Resistance is both a snapshot of a particular literary moment and a call to action: "Do yourself and ten million Hungarians a favor. Don’t allow the brilliant work of László Krasznahorkai to remain in obscurity. Put this newspaper down, brave the cold and go buy a copy of The Melancholy of Resistance. Make no mistake: it’s a difficult book, but a vastly rewarding one."

With the Nobel now in hand, Krasznahorkai joins Imre Kertész—who won in 2002—as the second Hungarian laureate in literature. The honor is, as the Swedish Academy noted, a recognition of a body of work that sees through the "fragility of the social order" while maintaining an unwavering belief in art. For Krasznahorkai, who once said, "Writing, for me, is a totally private act," the world’s attention may feel like an intrusion. But for readers, new and old, it’s an irresistible invitation into the labyrinthine, haunting beauty of his prose.