A study recently published in Scientific Reports examines the correlation between neighborhood walkability and cardiometabolic disease (CMD) measures among residents in Texas, revealing significant health implications tied to the physical environment.

Cumulatively, cardiometabolic diseases, which include conditions like diabetes and heart disease, affect a substantial number of adults in the United States. Recent statistics indicate that approximately 11% of the American population suffers from diabetes and around 10% has cardiovascular diseases. In Texas, this issue is particularly pressing, as state health indicators reveal a dire need for strategies to combat these prevalent conditions.

Research conducted by Mengyang Yang and Tiantian Wang utilized data from the Texas Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the Environmental Protection Agency, collecting observations from nearly 2,000 residents in 2019. This massive dataset enabled the researchers to perform multilevel linear and logistic regression analyses to assess how neighborhood walkability correlates with various CMD measures while controlling for factors like age, sex, racial and ethnic background, and family history of diabetes.

One of the key findings revealed that neighborhoods deemed more walkable are significantly associated with lower body mass index (BMI) levels among residents, as indicated by a regression coefficient (β) of -0.28, with a confidence interval of -0.45 to -0.10. Simply put, for every unit increase in walkability, a person's BMI is expected to decrease by about 0.28 kg/m². The implications of this metric are profound given the relationship between obesity, diabetes, and other chronic health conditions.

Moreover, the study reported that increased walkability is linked to a 7% reduction in the odds of individuals having diabetes (odds ratio 0.93, confidence interval 0.86–0.99). As the authors noted, “an increase of one unit in walkability reduces the odds of having diabetes by 7%.” This finding underscores the critical role that a well-designed, accessible environment plays in encouraging physical activity, thus improving overall health outcomes.

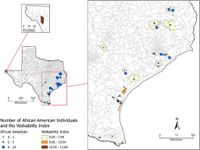

Additionally, the research investigates the influence of racial and ethnic backgrounds on neighborhood walkability. The researchers identified a concerning trend whereby African American communities are frequently located in areas with lower walkability scores compared to their Hispanic counterparts. In fact, the study revealed that the average walkability score for African Americans was significantly lower (mean = 7.04) than that for Hispanics (mean = 8.62), indicating structural disparities that could impact health outcomes.

The National Walkability Index, a key component of the study, scales walkability from 1 to 20 based on various environmental factors such as street design and proximity to amenities, providing a nuanced view of how well neighborhoods support walking as a mode of transport. The lower scores observed in African American neighborhoods may reflect broader socioeconomic inequalities and suboptimal urban planning decisions that fail to prioritize health and accessibility.

Previous studies corroborate the findings from this research. Individuals living in highly walkable neighborhoods tend to engage in more physical activity and have lower rates of diabetes and obesity. The correlation between walkability and lower cardiometabolic risks is significant enough to influence public health policy and urban development strategies.

Understanding this relationship is not only essential for public health advocates but also for urban planners aiming to create healthier community spaces. The authors propose that plans aimed at increasing neighborhood walkability could substantially enhance public health initiatives, particularly for communities that currently experience barriers to physical activity.

While this study brings to light crucial associations, it also outlines certain limitations. Notably, the research is cross-sectional, which means it would benefit from longitudinal studies to establish causality over time. Additionally, gathering more granular data on physical activity levels could provide deeper insights into how walkability impacts health metrics.

In conclusion, the findings from Yang and Wang indicate that fostering communities that prioritize walkability can lead to substantial public health benefits. With rising rates of obesity and diabetes, particularly within African American communities, enhancing neighborhood infrastructure to encourage walking is a pivotal strategy for mitigating these public health crises. The diversity of study participants strengthens its findings, informing future research and policy development aimed at lessening the burden of cardiometabolic diseases in Texas and beyond.