Florida has found itself at the center of a heated debate over the death penalty, grappling with questions of fairness, effectiveness, and the sheer pragmatism of capital punishment. According to the Tallahassee Democrat, the state currently leads the nation in executions for 2025, having put nine people to death so far this year, with two more scheduled before the end of August. These numbers are stark, but they tell only part of the story—a story marked by decades-long delays, legal wrangling, and a system that many argue is anything but just.

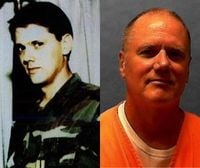

The recent execution of Edward Zakrzewski on July 31, 2025, for the murders of his wife and two children, serves as a sobering example. As reported by the Tallahassee Democrat, Zakrzewski’s execution came 31 years after his crimes. He was not alone in this lengthy wait: all nine men executed in Florida this year had been on death row for over 20 years, with three waiting approximately 30 years for their sentences to be carried out. This reality raises a fundamental question: can a punishment that is delayed for decades still be considered a deterrent?

"How can any punishment deter any crime if the reality is, 'You kill that guy, and we’ll kill you 30 years from now?'" the Tallahassee Democrat asks, capturing the frustration felt by both supporters and opponents of capital punishment. The intended swiftness and finality of the death penalty have been replaced by a slow, grinding process that seems to serve neither justice nor public safety.

Florida’s history with the death penalty is long and complicated. Since John Spenkelink became the first person in modern times to die in the state’s electric chair on May 25, 1979, Florida has executed 114 more individuals. The system has undergone numerous reforms over the years. After the U.S. Supreme Court halted executions nationwide in 1972, then-Governor Reubin Askew, a former state prosecutor, took months to consult with Floridians on all sides before agreeing to a limited law intended to end the "freakish and whimsical" application of capital punishment—a phrase that still haunts today’s debates.

Despite these reforms, including the switch from the electric chair to lethal injection, tighter court deadlines, and the introduction of a two-stage trial process (first establishing guilt, then deciding life or death), the problems persist. Most recently, Florida reduced the jury vote requirement for recommending a death sentence from unanimity to an 8-4 majority, a move intended to expedite the process but one that has drawn criticism from those concerned about fairness and the risk of wrongful convictions.

The risk of error is not merely theoretical. Florida has a troubling record of death row exonerations, described by the Tallahassee Democrat as a "chilling record of 'exonerations'—a comforting way of saying 'Oops!'" Each exoneration is a stark reminder of the system’s fallibility. The courts, mindful of these risks, insist on exhaustive due process, which in turn contributes to the decades-long delays between conviction and execution.

Governor Ron DeSantis and many Republican legislators have made no secret of their desire to speed up executions. Campaign ads often tout candidates’ plans to accelerate the process, sometimes implying that their opponents are soft on crime or unsympathetic to victims. Yet, as the Tallahassee Democrat notes, "the courts insist on all that due-process stuff." The legal system’s insistence on thorough review is not just bureaucratic red tape; it’s a safeguard against irreversible mistakes.

Efforts to abolish the death penalty altogether have surfaced from time to time, with proposals to replace it with mandatory life imprisonment. However, these bills have never advanced beyond the committee stage, reflecting the deep political and cultural divisions that surround the issue in Florida. Death penalty opponents often find themselves defending against accusations of being soft on crime or indifferent to the suffering of victims and their families.

The political theater extends to the legislature, where, as the Tallahassee Democrat recounts, lawmakers have sometimes proposed extreme measures—such as executing killers in the same manner as their crimes—only to reconsider after the initial show of toughness. The media, too, can play a role in this spectacle, sometimes reducing the issue to a tally of death warrants signed by the governor, as if it were a competition rather than a matter of life and death.

But beneath the posturing lies a more troubling reality. The application of the death penalty in Florida remains, as critics argue, "freakish and whimsical." The outcome of a capital case can depend on factors as arbitrary as which judge hears the case, the quality of legal representation, whether a codefendant can make a deal, or even the timing of a governor’s term. "Your life shouldn’t depend on which judge hears your case, or how good a lawyer you get, or whether you have a codefendant to flip on, how sympathetic your victim was, or who’s governor when your appeals run out," the Tallahassee Democrat observes.

This unpredictability undermines the very notion of justice. Even as legislators continue to "tinker" with the system—tightening deadlines here, lowering jury vote thresholds there—the core problems remain unresolved. The death penalty continues to be expensive, slow, and, in many cases, ineffective at achieving its intended goals. The cost is not just financial but moral, as the state risks executing the wrong person or applying its ultimate punishment unevenly.

Supporters of the death penalty often cite the need for retribution and justice for the most heinous crimes. There is, as the Tallahassee Democrat acknowledges, "logical justification for executions" if revenge is seen as a proper purpose of the law. But the duty to "get it right, every time" is a weighty one—perhaps too heavy for any legal system shaped by human fallibility and subjectivity.

As Florida continues to lead the nation in executions, the debate shows no sign of abating. The state’s experience serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the perils of a system that is at once slow to deliver justice and prone to error. For now, the questions linger: Can the death penalty ever be fair? And if not, why does it endure?

In the end, Florida’s struggle with capital punishment is less about toughness on crime and more about the enduring challenge of balancing justice, fairness, and the irrevocable consequences of getting it wrong.