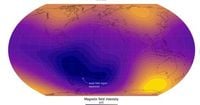

Earth’s magnetic field, the invisible force that shields our planet from the relentless bombardment of cosmic radiation and charged solar particles, is showing signs of dramatic change. Over the last eleven years, scientists have observed a weak spot in this protective shield—known as the South Atlantic Anomaly—expanding at an accelerated pace, raising questions about what’s happening beneath our feet and what it means for technology orbiting above.

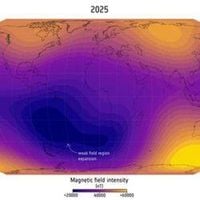

On October 13 and 14, 2025, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced the results of a comprehensive study, published in the November issue of Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. Drawing from over a decade of data collected by ESA’s Swarm satellite constellation, researchers revealed that the South Atlantic Anomaly—a region of weakened magnetic field strength stretching over the South Atlantic Ocean, South America, and now toward the tip of Africa—has grown by an area nearly half the size of continental Europe, or roughly two million square miles.

What exactly is the South Atlantic Anomaly, and why does it matter? According to ESA and NASA, the anomaly is a dip in Earth’s magnetic field, first detected in the 19th century, though it became a focus of concern in 1958 when satellites began measuring space radiation. The field dips to just 120 miles (200 kilometers) above the surface in this region, compared to the global average of about 400 miles (650 kilometers). This drop exposes satellites and spacecraft passing overhead to increased levels of charged particles and radiation, which can disrupt their operations, cause technical failures, and even lead to temporary blackouts.

The Swarm mission, comprising three identical satellites, has been tracking the planet’s magnetic signals since 2013. The constellation’s eleven-year data set provides the clearest picture yet of how the anomaly is evolving. “The South Atlantic Anomaly is not just a single block,” explained Chris Finlay, lead author of the study and Professor of Geomagnetism at the Technical University of Denmark, in statements to ESA and Live Science. “It’s changing differently towards Africa than it is near South America. There’s something special happening in this region that is causing the field to weaken in a more intense way.”

Satellite data shows that since 2020, the rate of weakening has increased, with the anomaly developing a distinct lobe stretching toward Africa—where the magnetic field is deteriorating fastest. Scientists believe this odd behavior is linked to mysterious fluctuations at the boundary between Earth’s liquid outer core and the mantle. Deep beneath the surface, the outer core is a swirling ocean of molten iron, generating electrical currents that in turn create Earth’s magnetic field. Normally, magnetic field lines emerge from the core and extend outward. But in the anomaly region, some of these lines are looping back into the core—a phenomenon called a reverse flux patch.

“Normally we’d expect to see magnetic field lines coming out of the core in the southern hemisphere,” Finlay told EarthSky. “But beneath the South Atlantic Anomaly we see unexpected areas where the magnetic field, instead of coming out of the core, goes back into the core. Thanks to the Swarm data we can see one of these areas moving westward over Africa, which contributes to the weakening of the South Atlantic Anomaly in this region.”

While the anomaly’s expansion has garnered attention, it’s not the only change in Earth’s magnetic field. The Swarm satellites also detected shifts in regions of unusually strong magnetic field, particularly in the northern hemisphere. Over Siberia, the strong spot has grown by an area equivalent to the size of Greenland, while the once-prominent strong region above Canada has shrunk by an area nearly the size of India. These changes are believed to be associated with the movement of the northern magnetic pole toward Siberia in recent years, further highlighting the dynamic nature of the planet’s magnetic environment.

What does this mean for life on Earth? For most people, the answer is: not much to worry about. “Changes in Earth’s magnetic field have less direct impact on humans, because the Earth’s thick atmosphere absorbs the majority of these charged particles, so they don’t reach the Earth’s surface,” Finlay explained in his interview with EarthSky. “There is nothing for people to be alarmed about here; this gradual change has been taking place at a similar rate for many decades. Now, thanks to the Swarm satellite observations, we just have a much better picture of how this is taking place.”

However, for the thousands of satellites now in orbit—and for astronauts aboard the International Space Station and China’s Tiangong space station—the stakes are higher. Spacecraft that pass through the South Atlantic Anomaly are exposed to increased radiation, which can disrupt onboard electronics, degrade solar panels, and increase the dosage of radiation received by astronauts. These effects can shorten satellite lifespans and necessitate additional shielding or operational precautions.

Navigation systems on Earth, too, are affected by the shifting magnetic field. Many everyday devices, from smartphones to aircraft navigation systems, rely on models of Earth’s magnetic field for orientation. As the field changes, these models must be updated—typically every five years—to ensure accuracy. “The main implication for us is in terms of our navigation systems,” Finlay noted. “The models of Earth’s magnetic field used in these systems need to be regularly updated, typically about once every five years, to account for the ongoing changes in the field geometry.”

Scientists are eager to continue monitoring these changes. ESA’s Swarm satellites remain healthy and are expected to keep collecting data well beyond 2030, providing researchers with an unprecedented view into the planet’s shifting magnetic landscape. “It’s really wonderful to see the big picture of our dynamic Earth thanks to Swarm’s extended timeseries,” said Swarm mission manager Anja Strømme in ESA’s statement. “The satellites are all healthy and providing excellent data, so we can hopefully extend that record beyond 2030, when the solar minimum will allow more unprecedented insights into our planet.”

So, should we be concerned about the growing South Atlantic Anomaly? The consensus among scientists is clear: while the changes are fascinating and have real implications for space-based technology, they do not pose a threat to life on Earth’s surface. Instead, they offer a unique opportunity to better understand the restless forces at work deep within our planet—and to appreciate just how dynamic, and occasionally unpredictable, our world can be.