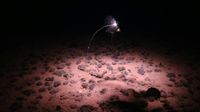

The seabed in the cold, lightless Pacific Ocean deep is scattered with metal-rich rocks, coveted by miners—and it also hosts a unique and diversified array of species. In the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), stretching between Hawaii and Mexico, researchers are racing to name thousands of species that are nearly unknown to science.

Once thought to be an underwater wasteland, the CCZ is now recognized as a treasure trove of biodiversity. It houses tiny worms, floating sponges, and even a giant sea cucumber affectionately described as the "gummy squirrel." This biodiversity, campaigners argue, is the true treasure of Earth's largest and least understood marine environment. The mining industry, however, is keen to extract the potato-sized nodules that contain precious metals needed for emerging technologies like smartphones and electric vehicle batteries, raising alarms about potential species extinction before they are even discovered.

According to marine researcher Tammy Horton of Britain's National Oceanography Centre (NOC), the need for responsible exploration has never been clearer. "We have a far greater understanding of that part of the world than we would have had if we weren't trying to exploit it," she said. In recent years, scientific efforts have expanded, scooping sediment and deploying remote vehicles to capture images and samples from the seafloor. Yet, despite revealing an impressive variety, the same patch of seafloor rarely showcases the same creature twice. This raises questions about the extent of biodiversity, as Horton noted, "There are huge numbers of rare species," particularly among mud-dwelling organisms.

A major breakthrough came in 2023 when a stocktake of data from scientific explorations found that approximately 90 percent of 5,000 recorded animal species were new to science. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has set an ambitious target: over a thousand species should be described by 2030 in the areas targeted by miners.

Describing and cataloguing these animals is painstaking work. Each must be sketched, dissected, and assigned a molecular barcode, allowing researchers to identify them in future studies. It took Horton and her specialists an entire year to describe just 27 of the more than a hundred unnamed amphipods, which are small crustaceans.

The work of mapping out the baseline of life in the abyssal plain is crucial for assessing potential ecological damage from mining activity. Conservation group Fauna & Flora warns of the wide-ranging impacts, from disrupting ocean food webs to exacerbating climate change by stirring up sediment that locks away carbon. The ISA is on track to finalize its international seabed mining code this year; however, concerns over the damage are mounting, as the first mining test site, plowed in 1979, still bears the marks of human activity more than 40 years later. NOC researcher Daniel Jones, who evaluated the site in 2023, noted that while there was some biological recovery, the ecosystem had not returned to its original density.

The minerals extracted from these nodules—such as cobalt and nickel—are increasingly crucial as the world transitions to renewable energy technologies. Yet the European Academies of Science Advisory Council (EASAC) cautions against overestimating their necessity, urging a halt to deep-sea mining until the long-term impacts are better understood. EASAC Environment Director Michael Norton aptly cautioned, "Once you go down it, you won't turn around willingly."

Meanwhile, in another corner of the Pacific, the deep midwater zone—a realm where creatures glow and life withstands immense pressure—is intertwined with surviving ecosystems. This region, which begins 650 feet beneath the surface, includes species vital for maintaining marine food webs, including commercially valuable fish such as tuna and whales, who rely on midwater animals for sustenance.

As companies seek these undersea treasures, scientists highlight risks posed to the midwater ecosystem through sediment plumes generated by mining operations. These plumes could interfere with animal feeding, impact biodiversity, and ultimately change the behaviors of these ocean dwellers. As an oceanographer closely monitoring the CCZ, I emphasize the need for caution before humanity pursues these resources indiscriminately. Can we justify sacrificing a fragile and poorly understood ecosystem for immediate technological gains?

Since the 1970s, exploratory deep-sea mining activities have surged, with the International Seabed Authority (ISA) being established in 1994 to oversee regulations. Yet it was only in 2022 that the first full test of an integrated nodule collection system occurred in the CCZ, carried out by The Metals Company and Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. These companies are slated to submit their application for full-scale mining to the ISA by June 27, 2025, with critical discussions planned for July 2025 to address mining regulations and environmental actions.

Currently, the process remains invasive: collector vehicles scrape the ocean floor, displacing habitats and threatening marine species' survival. The slurry of crushed nodules and sediment is often dumped back into the water column, causing sediment plumes that could extend the negative impacts deep into the ocean. Some operators even propose releasing waste at midwater depths around 4,000 feet, raising new ecological concerns.

A 2023 study revealed that a staggering 88% to 92% of species in the CCZ are foreign to science. With the ISA poised for substantial decisions regarding future mining prohibitions in July 2025, outstanding uncertainties linger over biodiversity loss and ecosystem disintegration. Without broad studies scrutinizing the impacts of mining on these coastal habitats, critical decisions based on limited understanding could permanently harm these delicate ecosystems.