Memory is a crucial cognitive function that deteriorates with age. However, this ability is assessed through cognitive tests instead of the architecture of brain networks. Researchers have now used reservoir computing, a recurrent neural network computing paradigm, to evaluate linear memory capacities of neural-network reservoirs derived from brain anatomical connectivity data in a lifespan cohort consisting of 636 individuals. The results reveal that computational memory capacity is a robust marker of aging, associated with resting-state functional activity, white matter integrity, locus coeruleus signal intensity, and cognitive performance. These findings were replicated in an independent cohort of 154 young and 72 old individuals, suggesting that reservoir computing can elucidate brain aging and associated disorders.

The complexity of the human brain enables effective communication across interconnected regions, collectively forming the connectome, which is vital for cognitive functions. In younger individuals, this connection organization is efficient, balancing local and distant interactions for optimal information processing. However, as we age, the organization deteriorates, hindering cognitive capabilities. Until now, the impact of these changes on the brain's computational capacity to process, learn, and encode information has been unclear, but this research has shed light on it.

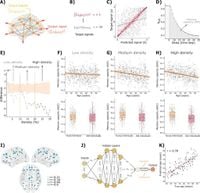

The research specifically uses reservoir computing to characterize how human cognitive function declines with age. Here, a computational model employs a network of artificial neurons representing various brain regions, constrained by individual anatomical connectivity. The model evaluates how effectively the network can replicate random time-dependent input signals, leading to the discovery of an optimal density for predicting individual age.

Notably, this study identified significant differences in computational memory capacity between young and old individuals, suggesting that memory capacity diminishes as aging progresses. Furthermore, remarkably high correlations between memory capacity and cognitive performance were observed, indicating that computational memory capacity might serve as a sensitive imaging biomarker for age-related cognitive decline.

In essence, as people age, the structural integrity of their brain networks begins to decline, particularly in the frontal and parietal regions. The results of this research suggest that these regions, vital for executive functions like decision-making, are highly affected by memory capacity reduction. Interestingly, some regions appear to compensate for this loss, indicating a complex adaptive response in brain behavior despite declining overall capacity.

Supporting evidence from the study indicates that age-related memory capacity decreases can act as reliable indicators of individual cognitive aging, with advanced machine learning techniques confirming these findings across different cohorts. With no significant distinctions based on sex, researchers believe this work opens up new possibilities for diagnosing and treating age-related brain disorders.

In conclusion, understanding the computational dynamics of memory capacity in the human brain through an innovative reservoir computing framework provides significant insights into brain aging. As researchers continue to explore this connection, developing techniques involving computational models could eventually enhance our capabilities to evaluate neurological disorders, paving the way for novel therapeutic options.