Climate change is impacting not only the environment but also the agricultural crops we rely on, significantly altering the chemical makeup of key forage legumes like red clover and cowpea. A recent study published in Scientific Reports examined how short-term exposure to elevated temperature and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels affects phytoestrogen concentrations—plant compounds analogous to the mammalian hormone estrogen—in these legumes.

Phytoestrogens are naturally occurring secondary metabolites found predominantly in legumes such as red clover (Trifolium pratense) and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), which play significant roles in animal feed. Understanding the consequences of climate change on these compounds is pivotal, as excessive amounts can impact the reproductive performance of livestock. Researchers conducted their experiments under controlled conditions to simulate the expected climate projections for the coming years.

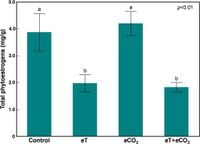

The study, led by Palash Mandal and colleagues from the University of New Hampshire, involved growing red clover and cowpea plants under different conditions representing elevated temperature (eT) and CO2 (eCO2). These involved maintaining plants at ambient settings (around 24°C and 400 ppm CO2) before exposing them to elevated temperatures of 35°C and CO2 levels of 750 ppm for ten days. The findings were notable: phytoestrogen concentrations were below detection levels for cowpea, and for red clover, exposure to higher temperatures alone reduced total phytoestrogen concentration by nearly 50%, from 3.9 to 1.9 mg/g dry matter.

Particularly concerning was the effect of elevated temperatures on specific isoflavones—key phytoestrogens within red clover. The concentrations of formononetin and biochanin A, the most abundant isoflavones, dropped by as much as 63% under eT and eCO2 conditions, indicating potential stress responses tied to abiotic stressors caused by climate change. Interestingly, the study found no significant influence of elevated CO2 alone on these compounds.

The physiological responses of plants to these environmental conditions varied. While cowpea displayed increased biomass and leaf area when grown under eCO2, red clover showed no significant growth differences under the stress treatments when compared to ambient control conditions. This suggests species-specific responses to climate change, highlighting the resilience of cowpea compared to more temperature-sensitive legumes like red clover.

The research highlights significant correlations between plant physiological measures and phytoestrogen concentrations, hinting at future agricultural practices where farmers might filter forage legumes based on physiological indicators to mitigate the risks of animal reproduction impairment associated with phytoestrogens. The authors expressed the need for broadening the scope of their future research since the emergence of isoflavones under environmental stress including drought or pest damage could add complexity to our current understandings.

With predictions indicating increased averages of over 2°C throughout the Northeast United States by 2035, the study points to serious repercussions for the concentration of phytoestrogens, particularly those known to influence livestock health. The researchers concluded, "Our findings suggest… short-term increases in atmospheric temperature associated with climate change may lead to overall reductions… factors affecting the phytoestrogens produced."2 They recommend more extensive longitudinal studies to flesh out the interplay between environmental factors and phytoestrogen biosynthesis, keeping livestock health and agricultural sustainability at the forefront of future research agendas.