Assata Olugbala Shakur, born JoAnne Deborah Byron and also known as Joanne Deborah Chesimard, died on September 25, 2025, in Havana, Cuba, at the age of 78. Her passing, confirmed by Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and her daughter Kakuya Shakur, marks the end of a life that was as remarkable as it was controversial. Shakur’s death was attributed to aging and health complications, bringing to a close over four decades spent in exile after a dramatic escape from a U.S. prison and a lifetime dedicated to Black liberation and political activism.

Shakur’s story is one of resilience, resistance, and relentless pursuit of justice as she saw it. Born in New York City on July 16, 1947, she spent her early years moving between Queens and Wilmington, North Carolina, experiencing firsthand the harsh realities of the Jim Crow South and the persistent racism of the North. In a 1998 letter to Pope John Paul II, she recalled, "I spent my early childhood in the racist segregated South. I later moved to the northern part of the country, where I realized that Black people were equally victimized by racism and oppression."

Her activism blossomed during her college years in the turbulent 1960s, where she became a pivotal organizer in student rights, Black liberation, and anti-war movements at Borough of Manhattan Community College and the City College of New York. She would go on to join the Black Panther Party and later the Black Liberation Army (BLA), groups that sought to challenge systemic racism and police brutality in the United States.

Shakur’s life took a dramatic turn in 1973 during a traffic stop on the New Jersey Turnpike. The encounter erupted in gunfire, leaving her friend Zayd Malik Shakur and State Trooper Werner Foerster dead. In 1977, after a highly publicized trial before an all-White jury, she was convicted of Foerster’s murder. Shakur always maintained her innocence, claiming, "I was shot once with my arms held up in the air and then once again from the back." She described her conviction as a "legal lynching," and insisted, "I have been a political activist most of my life, and although the US government has done everything in its power to criminalize me, I am not a criminal, nor have I ever been one."

Sentenced to life plus 33 years, Shakur’s time behind bars was short-lived. In 1979, with the help of armed allies posing as visitors, she escaped from the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women. Fearing for her life and convinced she would never receive justice in the United States, she fled the country. By 1984, she had resurfaced in Cuba, where Fidel Castro granted her political asylum, a decision that would become a sore point in U.S.-Cuba relations for decades. Despite repeated extradition requests from the U.S. government, Cuba refused to return her.

Shakur’s life in exile was anything but quiet. She became an icon for activists worldwide, her story and voice amplified through her writings, particularly her 1987 autobiography. The book became a staple for students of history and activists alike, with passages such as, "It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” Her influence extended into music and popular culture; she was the godmother of rapper Tupac Shakur and inspired artists like Public Enemy and Common.

Her unwavering stance against what she described as “U.S. imperialism, capitalism and dehumanization” made her a symbol of hope for some and a villain for others. In 2013, the FBI added her as the first woman to its Most Wanted Terrorists list, offering a $2 million reward for her capture. The U.S. government’s pursuit never ceased, and her case was repeatedly cited as an example of the fraught relationship between the United States and Cuba.

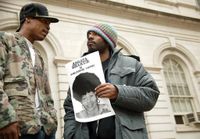

Shakur’s death has prompted an outpouring of tributes from activists, scholars, and organizations. Her daughter, Kakuya Shakur, wrote on Facebook, “Words cannot describe the depth of loss that I am feeling at this time. I want to thank you for your loving prayers that continue to anchor me in the strength that I need at this moment. My spirit is overflowing in unison with all of you who are grieving with me at this time.”

Many see her as a beacon for those fighting against injustice. June L. Lewis, a senior human rights defender and United Nations delegate, told the AFRO, "Sister Assata was the original ‘Soul sister,’ ebony, loud proud. A quiet carrier, pillar of the early Black Power movement, she fought a righteous cause. The world mourns a true inspiration to all marginalized peoples." Howard University professor Stacey Patton celebrated her freedom in death, stating, "The U.S. government, after decades of pursuit, never got the satisfaction of putting her in a cage. They wanted her bound, broken, and paraded as an example, but instead, she slipped their grip and lived out her life in exile, surrounded by people who honored her struggle and her survival. For racist white America, she was a fugitive. For us, she was a freedom fighter who refused to bow. Assata leaves this world with her dignity intact, her story unbent, and her defiance ETERNAL. She was never theirs to claim. She belonged to history, to the people, and to the ongoing fight for liberation. And now, she belongs to the ancestors."

Yet, for many in law enforcement and government, Shakur remained a wanted criminal. New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy and State Police Superintendent Patrick Callahan issued a joint statement expressing regret that she "passed without being held fully accountable for her heinous crimes," and vowed to "vigorously oppose any attempt to repatriate Chesimard’s remains to the United States."

Her passing has stirred reflections on the ongoing struggles for justice and equality. Dr. Karsonya Whitehead, president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, remarked, “From my days at Lincoln University when I first stumbled upon her work, up until today, she is what freedom looks like to me. She is what it looks like to stand up to this racist, sexist system and say ‘No, not me, not today.’ May she rest in peace and power.”

Organizations like CodePink and the Democratic Socialists of America have honored her as a symbol of hope and resistance, vowing to "honor her legacy by recognizing our duty to fight for our freedom, to win, to love, and protect one another because we have nothing to lose but our chains." Black Lives Matter organizer Malkia Amala Cyril lamented to the Associated Press that Shakur died during a global rise of authoritarianism, saying, “The world in this era needs the kind of courage and radical love she practiced if we are going to survive it.”

Assata Shakur’s life and death continue to evoke strong emotions and debates about justice, activism, and the meaning of freedom. Whether viewed as a champion of the oppressed or a fugitive from justice, her legacy is certain to endure, inspiring future generations to reflect on the complexities of resistance and the ongoing struggle for liberation.