Recent discoveries at the Tombos archaeological site in northern Sudan are reshaping our understanding of ancient Egyptian burial practices, suggesting that the iconic pyramids, long believed to serve exclusively as tombs for the elite, may also have been the final resting place for lower-status workers. This groundbreaking research was led by a team including Sarah Schrader, Michele Buzon, Emma Maggart, Anna Jenkins, and Stuart Tyson Smith, and has been detailed in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

The findings at Tombos date back approximately 3,500 years, coinciding with the period when Egypt expanded its influence southward. Here, scientists uncovered skeletons of individuals believed to be officials, scribes, or artisans, whose physical remains show signs of intense labor. These revelations challenge the traditional belief that pyramid burials were only for the affluent members of society.

“Our findings suggest that pyramid tombs, once considered the final resting places of the elite, may also have included low-status personnel with high labor demands,” explained Schrader. This means that contrary to long-held assumptions, the pyramid necropolises were not purely reserved for pharaohs and high-ranking nobles.

The skeletons found within the Tombos cemetery revealed an unexpected demographic. Many of the remains belonged to young adult males who had high levels of physical activity, indicating that they likely began working at a young age. This intensified work often pointed toward a lower socio-economic status, as indicated by the limited funerary objects and inexpensive cane coffins.

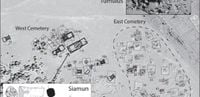

Importantly, previous studies have also highlighted the diversity within burial practices at Tombos. Analysis identified skeletons with varying degrees of physical exertion; some individuals seemed to hold a more laborious role, whereas others exhibited signs of less strenuous activities. The tombs where these remains were located varied in complexity, hinting at a more nuanced societal structure than previously acknowledged.

In examining these findings, the researchers emphasized the implication of social hierarchy as reflected in burial customs. “This, along with the scant funerary objects and cheap coffins, suggests that some individuals from the western cemetery may have belonged to a lower socioeconomic class,” noted Schrader in a report to National Geographic.

The analysis also challenged the notion that the status of an individual could always be easily assessed based on burial practices alone. Factors such as the location of burial and the presence of disturbance in the grave could complicate the evaluations made by archaeologists concerning an individual’s rank or status.

In a broader context, these discoveries contribute significantly to the ongoing discussions surrounding ancient Egyptian burial customs and the roles various societal classes played in monumental practices. Archaeological insights into this region have historically focused on elite burials, but findings such as those at Tombos suggest a much more complex web of relationships between the Egyptian rulers and their workforce.

The notion that the pyramids served as a networking point between social classes is an intriguing perspective and reflects a duality in the perception of labor and prestige in ancient cultures. Based on comparative studies with data from both Egypt and Nubia, the evidence supports the existence of mixed tombs, where the remains of workers were interred alongside those of elites—potentially offering them continued servitude in the afterlife.

“The tombs were seen as a continuation of service in the afterlife for workers buried alongside their masters,” stated Schrader, highlighting a fascinating aspect of ancient Egyptian beliefs about life after death.

The revelations from the Tombos site not only question the established narratives of ancient Egyptian burial customs but invite further archaeological inquiry into how we view the physical remnants of the past. As the researchers suggest, it is essential to continue excavating and analyzing the rich history buried beneath those iconic structures, persevering in uncovering the stories of those who contributed to the building of a civilization.

In conclusion, the Tombos discovery stands as a pivotal moment in Egyptology and pushes scholars to rethink their perspectives on social structure and burial practices in ancient Egypt. It underscores the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in archaeology, merging bioarchaeology and sociocultural studies to paint a more comprehensive history of this fascinating civilization.